Dalena sinh ra tại Muncie, Indiana và sống tại Orlando, Florida từ khi cô 3 tuổi, cô là con trong 1 gia đình người Mỹ trung lưu có 7 chị em (5 trai, 2 gái).

Dalena hát trong nhà thờ từ khi còn bé, nên dòng nhạc cô yêu thích và ảnh hưởng là dòng nhạc thánh ca.[2] Năm 16 tuổi cô bắt đầu biểu diễn tại một nhà hàng mang tên The Garden Spot Café, sau đó là nhà hàng People’s Place (ở Orlando).

Dalena có lần tâm sự: "VN đối với tôi là những món ăn ngon và hình ảnh cánh đồng trải dài cùng đàn cò trắng. Tuy mẹ tôi là người Mỹ nhưng bà nấu các món ăn VN rất ngon. Khi vào trung học, tôi quen với một vài người bạn VN. Qua họ, tôi hiểu hơn về tập tục của đất nước này".

Năm 1986, Dalena học đàn guitar của người thầy quê gốc ở Trà Vinh, nên sớm làm quen với các làn điệu dân ca. Ngay lập tức, cô say mê học đàn và bắt đầu tìm hiểu nội dung của những ca khúc tiếng Việt.

Ban đầu cô phải phiên âm từng chữ cái, cộng thêm vài hàng ghi chú bằng Anh ngữ. Cô biết hát tiếng Việt nhưng chỉ nói được rời rạc và lõm bõm một ít tiếng Việt, vì không có nhiều thời gian để học.

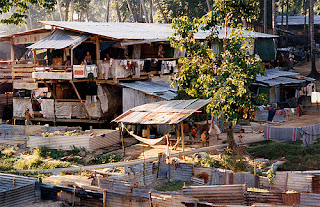

Năm 2003, Dalena từng tới Việt Nam biểu diễn và làm từ thiện, thời gian ở VN, Dalena đã đi thăm Trung tâm nuôi dưỡng bảo trợ trẻ em Gò Vấp và đã rất xúc động với hoàn cảnh của các em và nhân viên ở đây.

Cô bày tỏ mong muốn có dịp được trở lại Việt Nam để được giúp đỡ, chia sẻ với các em mồ côi, khuyết tật, ít nhất cũng đem tiếng hát làm vơi đi nỗi đau của các em.

Sự nghiệp biểu diễnSửa đổi - Dalena cho biết cô quyết định tập hát nhạc Việt từ năm 1990. Lúc mới tập, do không biết ngân theo giai điệu nhạc Việt, nên nghe có vẻ khô khan, nhưng rồi nhờ sưu tầm và thường xuyên nghe CD của các ca sĩ trẻ mà cô đã học được cách hát truyền cảm hơn.

www.facebook.com/ash.noka.77

Năm 1992, Dalena gây được chú ý qua album hát chung với Tuấn Ngọc, Đức Huy, Thái Châu, Đôn Hồ, Hương Lan... Ban đầu người ta xem cô hát vì hiếu kỳ, nhưng về sau, họ tin rằng có một người con gái Mỹ thực sự mang lại không khí ấm áp, dễ chịu cho người nghe qua chất giọng rất Việt Nam.

Năm 1991, cô ký thỏa thuận 6 tháng với hộp đêm Ritz nightclub - nằm tại nơi được mệnh danh là thủ phủ của người Việt - Florida, với cộng đồng người Việt đông đảo, chiếm phân nửa số người Việt tại Hoa Kỳ.

Hợp đồng thu âm đầu tiên của cô là với một studio nhỏ chủ người Việt.[4] Cho đến 1993, cô đã phát hành tới 5 album tiếng Việt và hát cho nhiều cộng đồng người Việt tại Hoa Kỳ và châu Âu cũng như các trung tâm băng đĩa phục vụ người Việt.

Dalena không chỉ hát tốt tiếng Anh, tiếng Việt mà thỉnh thoảng còn hát tiếng Trung Quốc, Nhật, Pháp, Tây Ban Nha, Hàn Quốc, Do Thái… Dalena còn hát những bài do chính cô sáng tác. Cô tự học guitar và có thể đệm đàn cho mình hát. Cách sáng tác của Dalena là tự đánh đàn, dùng máy ghi âm lại và sau đó nhờ nhạc sĩ ký âm.

Một số Album tiêu biểu của cô phải kể đến là: Chút ân tình mong manh, Lệ đã, Cỏ úa, Oh My Sweet Love, Love Songs 7, Cho người tình dấu yêu, Hoài mộng.

https://vi.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalena_Morton

Cơ sở chế biến Củ hủ Dừa khổng lồ ở Bến Tre | Củ hủ Dừa (The pith of coconut canopy hub food product)

...

...

Ca sĩ Dalena tên thật là Dalena Morton, sinh ra và lớn lên trong một gia đình người Mỹ trung lưu có 7 chị em tại Florida, nhưng cô lại trở thành ca sĩ hát tiếng Việt rất thành công.

Mặc dù có rất nhiều ca sĩ ngoại quốc hát nhạc Việt Nam, Dalena có lẽ là người thành công nhất và nổi tiếng nhất. Xem Dalena trình diễn trên sân khấu trong các băng video hoặc nghe cô hát, chúng ta không khỏi ngạc nhiên bởi giọng ca hoàn chỉnh và hình dáng duyên dáng của cô. Là một người Mỹ 100%, khi xem Dalena trình diễn, thật mà khó biết được nguồn gốc của cô. Năm 1986, Dalena học đàn guitar của người thầy quê gốc ở Trà Vinh, nên sớm làm quen với các làn điệu dân ca. Ngay lập tức, cô say mê học đàn và bắt đầu tìm hiểu nội dung của những ca khúc tiếng Việt.

Ban đầu cô gái người Mỹ này phải phiên âm từng chữ cái, cộng thêm vài hàng ghi chú bằng Anh ngữ. Thế giới âm nhạc mở ra cho Dalena một chân trời mới với hình ảnh, đất nước, con người Việt Nam qua những bài hát.

Dalena thích hát và sưu tầm những bài mang âm hưởng dân ca. Cô nói: “Tôi quyết định tập hát nhạc Việt từ năm 1990. Lúc mới tập, tôi không biết ngân theo giai điệu nhạc Việt, nên nghe có vẻ khô khan, nhưng rồi nhờ sưu tầm và thường xuyên nghe CD của các ca sĩ trẻ, tôi đã học được cách hát truyền cảm hơn.

Năm 1992, tôi gây được chú ý qua album hát chung với Tuấn Ngọc, Đức Huy, Thái Châu, Đôn Hồ, Hương Lan… Ban đầu người ta xem tôi hát vì hiếu kỳ, nhưng về sau, họ tin rằng có một người con gái Mỹ thực sự mang lại không khí ấm áp, dễ chịu cho người nghe qua chất giọng rất Việt Nam”.

Khi được hỏi về loại nhạc cô thích nhất, cô cho biết lúc đầu cô thích Thánh Ca. Cô tìm thấy niềm tin ở Chúa và sự khuyến khích từ mẹ cô cũng như những lá thư do khán thính giả mến mộ cô gửi đến. Dalena đã xuất hiện trên nhiều chương trình Paris By Night, Asia và đã nhận được rất nhiều ái mộ từ khán thính giả.

Cô đã trình bày một cách xuất sắc những nhạc phẩm như “Qua Cầu Gió Bay”, “Biển Nhớ”, “Mưa Trên Phố Huế”… Dalena đến với nhạc Việt Nam cũng do một sự tình cờ và hoàn toàn do chính bản thân tự luyện tập bằng cách nghe nhạc Việt và bắt chước cách phát âm từng chữ một. Là một người ngoại quốc nhưng cô luôn yêu mến người Việt cũng như văn hóa Việt.

Dalena cho biết: “Khi nhắc đến Việt Nam, đối với tôi là những món ăn ngon và hình ảnh cánh đồng trải dài cùng đàn cò trắng. Tuy mẹ tôi là người Mỹ nhưng bà nấu các món ăn Việt Nam rất ngon. Khi vào trung học, tôi quen với một vài người bạn Việt Nam. Qua họ, tôi hiểu hơn về tập tục của đất nước này”.

https://nhacxua.vn/dalena-nguoi-con-gai-my-voi-tam-hon-viet-nam/

There are a couple of different ways to approach your first all-grain brew day. There is a vast amount of information in the homebrew literature about all-grain brewing, and you could try to read most of it first and then proceed. Or, you could jump right in.

Learning to brew well at home requires some practical experience that you can only get by actually brewing on your equipment, with your water, etc.

Getting to know the mechanics of brewing — including the quirks of your setup — is just as important, in terms of beer quality, as knowing many of the more advanced academic ideas.

In this article, we'll cover the bare minimum of technical information you need to get started and give a practical guide to successfully brewing your first all-grain beer.

All-Grain Basics (The Minimum) - All-grain brewing differs from extract brewing mainly in the wort production stage. As an extract brewer, you made your wort by dissolving malt extract in water, and likely steeping some specialty grains to add some additional flavors.

As an all-grain brewer, you will make your wort from malted grains and water. The basic idea behind all-grain wort production is this: You soak crushed, malted grains in hot water to change starch into sugar, then drain away the resulting sugary liquid, which is your wort.

That's it. Once your wort has been created in the brew pot then everything can be handled in the same way as in extract brewing. The only caveat is that you need to do full volume boils and no longer have the ability to opt for partial boils. This can pose a few challenges that are tackled with a few extra pieces of equipment.

All-Grain Equipment - Traditionally all-grain homebrew set ups included three vessels. A more recent trend has moved a lot of brewers towards a more simplified Brew In A Bag (BIAB) format which is a single vessel set-up.

For this article, we will outline the traditional three vessel system, but if you are interested in the simplified BIAB technique, check out this BIAB article by John Palmer.

For a three vessel system, the first vessel is used to heat all the water for your brewing session. As brewing water is sometimes called brewing liquor, the name of this vessel is the hot liquor tank, or HLT.

Second, a vessel to hold the grains for both mashing (soaking the crushed grains) and lautering (separating the wort from the spent grains).

This is called a mash/lauter tun. (In commercial brewing, these are often separate vessels.) This needs to have a false bottom or some sort of manifold installed to let the wort flow from the vessel while retaining the spent grains. You will also need a large paddle to stir the mash (mash paddle). Lastly, you need a vessel to boil the wort in, called the kettle.

A 5-gallon (19 L) brewery can consist of three 10-gallon/40-quart (38-L) vessels. Systems such as this work well for most average to moderately-big brews.

If you don't already have a wort chiller, we recommend buying or building one. Quickly cooling your wort can help improve beer quality and help shorten your brew day.

Finally, you will need a heat source capable of boiling your entire pre-boil volume of wort vigorously. For 5-gallon (19-L) batches, you will need to boil at least 6 gallons (23 L), more if you want to make high-gravity beers.

For many all-grain homebrewers, the heat source of choice is a propane burner. Brewing with electric has become more and more popular with those folks who would prefer to brew indoors as has brewing with induction burners.

There are a lot of options when it comes to choosing all-grain equipment, too many to detail here. Keep in mind that great homebrew has been made on a wide variety of brewing setups.

Calibration and Calculations - Before your frist brew day, you should make a dipstick (or calibrate your sight glasses, if your brewery has those) so that you can measure the volume of liquid in your HLT and kettle.

Likewise, calibrate any thermometers that you will be using. For more on calibrating your equipment, click here for a more in-depth read.

Before starting any brew day, there are two easy calculations you should make — the amount of strike water (water to mix with the crushed grains) and the amount of sparge water (water to rinse the grain bed) you will need.

These are explained later in the Mashing In and Calculate Sparge Water sections, but to really hone in these calculations, we recommend this article from Bill Pierce.

Crushing the Grains - For your first all-grain brew, you will probably buy crushed malt or get the malt crushed at your homebrew shop. When it's time to brew, take a handful of malt and look at it. With a good crush, you should see almost no whole kernels. Most kernels should be broken into two to four pieces.

If you've bought, or have access to, a grain mill, you will gain experience over time adjusting it to get the best crush for you. For your first crush, however, see if the mill has a "default" setting. This is usually 0.045 inches (0.11 cm). This should give you a good crush and you can start fiddling with adjusting the mill gap when you get more experience.

The goal of the crush is to break the malt kernels open so that the hot strike water can dissolve the starchy endosperm in the malt. You don't need perfectly crushed grain to a have a successful first brew day, so don't worry about this too much.

Do, however, examine your crushed grains every time you brew. When the time comes to really start fine-tuning your brewing procedures, this will be valuable to you. Make a note in your brewing notebook about how the crush looked to you.

Mashing In - Once your equipment is set up, you will need to start heating your strike water (fancy term for the brewing water adding initially to the mash).

The amount of strike water required varies between 0.95 and 2.4 quarts of water per pound of grain (2–5 L/kg), and a good consistency — or mash thickness — for most beers is 1.25 and 1.375 qts./lb. (2.6-2.9 L/kg).

So, to figure out how much water you need, take the weight of your grains and multiply by some number between 1.25 and 1.375 (or 2.6 through 2.9, if you use the metric system).

The lower numbers will give you a little thicker mash than the higher numbers, although the specified range is all in the "moderate" range of mash thickness.

If your mash vessel has a false bottom, add the volume under your false bottom to the amount of strike water you need to heat. For example, if there is a gallon (3.8 L) of space under your false bottom, add this extra 1 gallon (3.8 L) of water to your strike water.

All-grain brews require heating larger volumes of water than most extract brews, so be prepared for this step to take longer than you might think. If you have a metal mash paddle, set it in the HLT while the strike water is heating.

Mixing the crushed grains and hot strike water is called mashing in. The goal is to mix the crushed malt and water so that the grain bed settles in at your target temperature (which will be given in the homebrew recipe) and that this temperature is as uniform as possible throughout the grain bed.

The initial temperature after mash in depends mostly on the temperature of the strike water, the temperature of the crushed malt and the temperature of your mash vessel.

There are equations that can help you calculate the temperature of your strike water, but most homebrewers "solve" this problem by using a generic recommendation and refining it with trial and error.

One generic recommendation works fairly well if your grain and equipment are in the vicinity of "room temperature," and you use a mash thickness between 1.25 and 1.375 qts./lb. (2.6-2.9 L/kg).

This is to heat your strike water to 11 °F (6 °C) above your target mash temperature. This assumes no, or minimal, heat loss when transferring your water to your mash tun.

Once you've heated the measured amount of strike water and transferred it to the mash vessel, check again to see that it's in the right range (9–10 °F/5–5.5 °C above your target).

Then, stir your crushed grains into the strike water. To do this, simply add a pound or so of grain to the water, give a quick stir with your mash paddle until it dissolves and repeat until all the grain is stirred in.

Stir the grain for 20–30 seconds, looking to even out any temperature differences and break up any clumps of dry malt sticking together. Then, take the temperature and place the lid on your mash tun to conserve heat.

Record the volume of the strike water, its temperature in your mash tun just prior to mashing in and the initial mash temperature. After several attempts, you will find an average temperature difference between the strike water temperature and the mash in temperature for your system.

Saccharification Rest/Starch Conversion - Now, you let the mash sit (or rest) for awhile. (The recipe should specify the length of this rest; often, it's one hour.) During the mash rest, your goal is to hold the grain bed at a constant, uniform temperature. Odds are, however, you won't be able to do this.

At a homebrew scale, the mash will lose heat over the time of the rest. And, the sides of the grain bed will cool off faster than the center. Fortunately, a small change in temperature is not going to hurt the quality of your beer.

After your first mash, quickly take the temperature near the side of the mash vessel, and then near the center. Stir the mash to even out any temperature differences and take the temperature again. Record all three temperatures in your brewing notebook.

If your overall mash temperature drops more than 2 °F (1 °C), or the temperature difference within the mash is greater than 4 °F (2 °C), you should insulate your mash tun better next time. You can use towels, sleeping bags or blankets for this. If your mash vessel is heatable, you can also add heat directly during the mash.

If you do, stir the mash and do not heat too quickly. More advanced all-grain systems often utilize a recirculated method of holding or heating the mash. If you are interested in recirculating systems, check out this article.

During the rest, you have the option of stirring. Stirring ensures a more even mixture of grain and liquid and evens out temperature differences across the grain bed. Unfortunately, opening the mash vessel releases heat to the environment. Likewise, using a "cold" mash paddle absorbs more heat from the mash.

As such, most homebrewers simply leave their mash undisturbed during this rest. (If you overshot your mash temperature by a few degrees, stirring a couple times is great way to gradually bring the temperature down.) Most homebrew recipes specify a one-hour rest for single infusion mashes.

Calculate Sparge Water - While the mash is resting, begin heating the water you will use to rinse the grain bed (the sparge water). How much sparge water will you need? We recommend heating an amount equal to the target pre-boil volume of your wort, plus about 20%.

This might seem like a huge amount, but this will allow you to collect your full pre-boil kettle volume, keep the grain bed in the mash/lauter vessel submerged throughout the wort collection process and have some extra water that serves as buffer against water in the "dead spaces" (tubing, etc.) loss to evaporation or small amounts of spillage.

Running out of sparge water is a pain, whereas leftover hot water can be used for cleaning equipment. So, err on the side of heating too much sparge water. For a 5-gallon (19-L) batch, this may mean 7.5 gallons (28 L) or more.

If you want to try to leave your grain bed dry at the end of sparging, subtract the volume of strike water from this amount. Also, if you mash out by adding boiling water to the grain bed (see the next section), subtract this volume from the required volume of sparge water.

Your goal should be for the sparge water to be at the correct temperature when the mash is over and the wort has been recirculated. Use the length of time it took to heat the strike water to estimate how long it will take to heat the sparge water.

Lautering Step 1: Mash Out (Optional Step) - At the end of the mash, you have the option of performing a mash out. To mash out, you raise the temperature of the grain bed to 170 °F (77 °C). Mashing out makes the wort less viscous, and easier to collect.

This can be done either by applying direct heat or by stirring in boiling water. If you heat the mash, be sure to stir as you do. If you add boiling water, you will need a volume that is approximately 40% of the volume of your strike water. Sometimes, the size of your mash tun will preclude you from adding enough water to reach 170 °F (77 °C).

This is fine as you can simply rinse with hotter sparge water to compensate for this. Once you arrive at 170 °F (77 °C), or have added all the water your mash/lauter tun will hold, let the grain bed rest for 5 minutes and then you are ready to recirculate. Record the details of your mash out — final temperature and volume of boiling water added (if any).

Lautering Step 2: Recirculation (Vorlauf) - The aim of recirculation is to draw some wort off from the bottom of the grain bed and return it to the top. Once enough wort has been recirculated in this way, the wort clears up substantially.

To recirculate manually, open the spigot to the mash/lauter tun slightly and slowly collect wort in a beer pitcher or similar vessel. Keep a timer running and collect wort at a rate that would fill the pitcher in about 5 minutes.

Once full, gently pour the pitcher back on top of the grain bed. Repeat this until the wort looks clearer or 20 minutes have passed. Some homebrew rigs allow you to recirculate using a pump.

Lautering Step 3: Sparging (Wort Collection) - Once recirculation is finished, it's time to start collecting wort. In this article we cover the traditional continuous or fly-sparging technique. For a more simplified batch sparge technique, check out Denny Conn's article found here.

To start your continuous sparge, slowly open the valve on your mash/lauter tun and let the wort start trickling in to the kettle. If your lauter tun is not positioned above the kettle, you can let the wort flow into a pitcher and then pour wort into the kettle.

Collect the wort at a rate such that takes about 60–90 minutes to collect the entire volume. To do this, keep the dip stick in the kettle and check on it every few minutes. Write down the time you start collecting wort and the time you cross the 1-gallon mark, 2-gallon mark, 3-gallon mark, etc.

The basic idea with continuous sparging is to apply water to the top of the grain bed at the same rate as it drains from the lauter tun. In theory, that should be simple. In practice it can be hard to match the flow rates.

A simple way around this problem is to focus on getting the flow rate from the mash/tun to the kettle correct, then apply sparge water at a faster rate in intermittent bursts. On my old setup, I used to pour a couple pitchers of water on top of the grain bed, then, about 10 minutes later — right before the grain bed would be exposed — I'd add another two pitchers.

During this time, wort would be flowing from the lauter tun to the kettle at a steady rate. Now, I do essentially the same thing by turning on and off my pump.

Addding your sparge water in "pulses," rather than trying to get the flow rate to match the outflow from your mash/lauter tun is simple and lets you focus how fast your kettle is filling.

Some more savy homebrewers set up a float switch, similar to those found in your toilet. The float switch will add water at the appropriate level to keep the flow from the hot liquor tank even with flow to the kettle.

You should heat your sparge water to the point that, as you sparge, the temperature of the grain bed approaches 170 °F (77 °C). If you mashed out to 170 °F (77 °C), and your lauter tun was well insulated, your sparge water should be 170 °F (77 °C) at the point that it is added. In this case, it may have to be hotter than 170 °F (77 °C) in the HLT if it travels through tubing (where it will lose temperature) on the way to your lauter tun.

If your grain bed is cooler than this, then sparging with water at 190 °F (88 °C) or higher is appropriate until the grain bed reaches 170 °F (77 °C). Write down the details of your sparging in your brewing notebook.

When to Stop Sparging - There are a few ways to determine when to stop collecting your wort. For average-strength beers, the easiest way is just to quit collecting when you've got the full pre-boil wort volume in your kettle.

With a propane burner, on homebrew-sized batches you can expect to boil off about a gallon an hour with a full rolling boil. So, for a 5-gallon (19 L) batch, you could collect 6 gallons for a one-hour boil or 6.5 gallons for a 90-minute boil.

A better way to know when to stop collecting wort is to monitor when you've gotten everything you reasonably can from the grain bed. The easiest way to do this is to take the specific gravity of your late runnings (the stream of wort you are collecting from the grain bed) and wait until they fall to about 1.008-1.010.

If you do this, you may end up with more or less wort than your planned pre-boil wort volume. If you are low, as happens on many low-gravity brews, just add water. If you have collected more wort than you planned, you can extend the length of your boil.

When you are done collecting wort, write down the volume of wort in your kettle, the time you quit collecting and the original gravity of the wort. Also record if you needed to add any water to reach your target pre-boil volume.

Boiling the Wort and Beyond - For extract brewers who do full wort boils, the rest of your brew day is identical to what you are used to. If you are looking to build a wort chiller, here are two easy projects to make one yourself. If not, just expect that heating and cooling a larger volume of wort will take longer.

Now you've got your first all-grain brew day under your belt. You also have a record of all the relevant volumes, temperatures and times of your first all-grain batch. Before you grab a celebratory beer, write down any other observations that you feel may help you with future brews.

Later, before your second brew, review your notes and determine what aspects of your brew day you want to improve upon. Knowledge comes quickly at first, so be sure to write absolutely everything down for your first several beers.

So now that we've covered the basics of your first all-grain and you're now chomping at the bit, ready for more information. Well, good news, we have the solution. Check out our special issue, the Best of Brew Your Own's Guide to All-Grain Brewing. You can ask for it at your local homebrew supply retailer as well.

Fat Tire Amber Ale

(5 gallons, all-grain)

OG = 1.050 FG = 1.011

IBU = 19 SRM = 14 ABV = 4.8%

Ingredients:

8 lbs. 10 oz. (3.9 kg) 2-row pale malt

1 lb. (0.45 kg) Munich malt

6 oz. (170 g) Victory® malt

8 oz. (227 g) crystal malt (40° L)

2 oz. (57 g) pale chocolate malt

4.4 AAUs Target pellet hops (60 min.) (0.4 oz./11 g at 11% alpha acid)

2.5 AAUs Willamette pellet hops (10 min.) (0.5 oz./14 g at 5% alpha acid)

0.5 oz. (14 g) Goldings pellet hops (0 min.)

Wyeast 1792 (Fat Tire Ale), Wyeast 1272 (American Ale II) or White Labs WLP051 (California Ale V) yeast

3/4 cup corn sugar (if priming)

Step by step: Heat strike water to roughly 166 °F (74 °C). Mash grains in 3.25 gallons (12.4 L) of water at 154 °F (68 °C) for 45 minutes. Lauter collecting roughly 6 gallons (23 L) of wort in your brewpot. Bring to boil and add Target hop pellets.

Boil for 50 minutes and add Willamette hop pellets. Boil 10 minutes longer and then add the Goldings hops. Remove from heat, give the wort a stir to create a whirlpool then let settle for 5 minutes.

Cool the wort to about 70 °F (21 °C) and transfer to fermenting vessel with yeast. Ferment 68 °F (20 °C) until complete, approximately 7 days.

At that point you can transfer to a secondary vessel, or condition for another week in primary. Rack into bottles or keg with corn sugar. (Try lowering the amount of priming sugar to mimic the low carbonation level of Fat Tire.) Lay the beer down for at least a few weeks to mellow and mature for best results.

https://byo.com/newbrew/all-grain/

With queens that can grow to 2 inches long, Asian giant hornets can use mandibles shaped like spiked shark fins to wipe out a honeybee hive in a matter of hours, decapitating the bees and flying away with the thoraxes to feed their young.

For larger targets, the hornet’s potent venom and stinger — long enough to puncture a beekeeping suit — make for an excruciating combination that victims have likened to hot metal driving into their skin.

In Japan, the hornets kill up to 50 people a year. Now, for the first time, they have arrived in the United States. McFall still is not certain that Asian giant hornets were responsible for the plunder of his hive.

But two of the predatory insects were discovered last fall in the northwest corner of Washington state, a few miles north of his property — the first sightings in the United States.

Scientists have since embarked on a full-scale hunt for the hornets, worried that the invaders could decimate bee populations in the United States and establish such a deep presence that all hope for eradication could be lost.

“This is our window to keep it from establishing,” said Chris Looney, an entomologist at the Washington State Department of Agriculture. “If we can’t do it in the next couple of years, it probably can’t be done.”

On a cold morning in early December, 2 1/2 miles to the north of McFall’s property, Jeff Kornelis stepped on his front porch with his terrier-mix dog. He looked down to a jarring sight: “It was the biggest hornet I’d ever seen.”

The insect was dead, and after inspecting it, Kornelis had a hunch that it might be an Asian giant hornet. It did not make much sense, given his location in the world, but he had seen an episode of the YouTube personality Coyote Peterson getting a brutal sting from one of the hornets.

Beyond its size, the hornet has a distinctive look, with a cartoonishly fierce face featuring teardrop eyes like Spider-Man, orange and black stripes that extend down its body like a tiger, and broad, wispy wings like a small dragonfly.

Kornelis contacted the state, which came out to confirm that it was indeed an Asian giant hornet. Soon after, they learned that a local beekeeper in the area had also found one of the hornets.

Looney said it was immediately clear that the state faced a serious problem, but with only two insects in hand and winter coming on, it was nearly impossible to determine how much the hornet had already made itself at home.

Over the winter, state agriculture biologists and local beekeepers got to work, preparing for the coming season. Ruthie Danielsen, a beekeeper who has helped organize her peers to combat the hornet, unfurled a map across the hood of her vehicle, noting the places across Whatcom County where beekeepers have placed traps.

“Most people are scared to get stung by them,” Danielsen said. “We’re scared that they are going to totally destroy our hives.” Adding to the uncertainty — and mystery — were some other discoveries of the Asian giant hornet across the border in Canada. In November, a single hornet was seen in White Rock, British Columbia, perhaps 10 miles away from the discoveries in Washington state — likely too far for the hornets to be part of the same colony.

Even earlier, there had been a hive discovered on Vancouver Island, across a strait that probably was too wide for a hornet to have crossed from the mainland.

Crews were able to track down the hive on Vancouver Island. Conrad Bérubé, a beekeeper and entomologist in the town of Nanaimo, was assigned to exterminate it.

He set out at night, when the hornets would be in their nest. He put on shorts and thick sweatpants, then his bee suit. He donned Kevlar braces on his ankles and wrists.

But as he approached the hive, he said, the rustling of the brush and the shine of his flashlight awakened the colony. Before he had a chance to douse the nest with carbon dioxide, he felt the first searing stabs in his leg — through the bee suit and underlying sweatpants.

“It was like having red-hot thumbtacks being driven into my flesh,” he said. He ended up getting stung at least seven times, some of the stings drawing blood.

The night he got stung, Bérubé still managed to eliminate the nest and collect samples, but the next day, his legs were aching, as if he had the flu.

Of the thousands of times he has been stung in his lifetime of work, he said, the Asian giant hornet stings were the most painful. After collecting the hornet in the Blaine area, state officials took off part of a leg and shipped it to an expert in Japan. A sample from the Nanaimo nest was sent as well.

A genetic examination, concluded over the past few weeks, determined that the nest in Nanaimo and the hornet near Blaine were not connected, said Telissa Wilson, a state pest biologist, meaning there had probably been at least two different introductions in the region.

Looney went out on a recent day in Blaine, carrying clear jugs that had been made into makeshift traps; typical wasp and bee traps available for purchase have holes too small for the Asian giant hornet.

He filled some with orange juice mixed with rice wine, others had kefir mixed with water, and a third batch was filled with some experimental lures — all with the hope of catching a queen emerging to look for a place to build a nest.

He hung them from trees, geotagging each location with his phone. In a region with extensive wooded habitats for hornets to establish homes, the task of finding and eliminating them is daunting.

How to find dens that may be hidden underground? And where to look, given that one of the queens can fly many miles a day, at speeds of up to 20 mph?

The miles of wooded landscapes and mild, wet climate of western Washington state make it an ideal location for the hornets to spread. In the coming months, Looney said, he and others plan to place hundreds more traps. State officials have mapped out the plan in a grid, starting in Blaine and moving outward.

The buzz of activity inside a nest of Asian giant hornets can keep the inside temperature up to 86 degrees, so the trackers are also exploring using thermal imaging to examine the forest floors. Later, they may also try other advanced tools that could track the signature hum the hornets make in flight.

If a hornet does get caught in a trap, Looney said, there are plans to possibly use radio-frequency identification tags to monitor where it goes — or simply attach a small streamer and then follow the hornet as it returns to its nest.

While most bees would be unable to fly with a disruptive marker attached, that is not the case with the Asian giant hornet. It is big enough to handle the extra load.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/

About Oxeye Daisy: The old name, Chrysanthemum leucanthemum, means "gold flower white flower." The new name, Leucanthemum vulgare means "common white flower." It is also known as bull daisy, button daisy, dog daisy, field daisy, goldens, marguerite, midsummer daisy, moon flower, and white weed.

Oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) is a beautiful flower, one that is both loved and hated. It was a plague on pastures and crop fields across Europe.

The Scots called the flowers "gools". The farmer with the most gools in their wheat field had to pay an extra tax. Now the gools have invaded this continent from coast to coast.

The lower leaves are spoon-shaped, while the upper leaves are narrow and clasp the stem. It can be confused with Shasta daisy (Leucanthemum x superbum/Chrysanthemum maximum), which can grow 6-12 inches taller and has larger flowers and foliage. Shasta daisy has a root ball, while oxeye daisy has a creeping root system.

It can also be confused with Scentless chamomile (Anthemis arvensis) , but the latter is an annual and has smaller flowers with much more finely dissected leaves. Oxeye likes rights-of-way, rangeland, mountain meadows, abandoned homesteads, and the edge of waterways.

The oxeye daisy is short-lived perennial originally brought here from Europe. The dainty flowers have escaped cultivation and now crowd out other plants on many rangelands. A vigorous daisy can produce 26,000 seeds per plant, while smaller specimens produce 1,300 to 4,000 seeds per plant.

Tests have shown that 82% of the buried seeds remained viable after six years, and 1% were still viable after 39 years. Oxeye daisy requires cold winters to initiate blooming. The plant also reproduces vegetatively with spreading rootstalks. Daisies are resistant to many herbicides.

Leucanthemum vulgare: Oxeye Daisy - Edibility: Eden Project's Emma Gunn in the blog post, How to forage and cook ox eye daisies gives a recipe for tempura battered oxeye daisies, sweet and savory snacks, and also suggests pickling the flowers.

Despite having a bitter taste, young leaves of oxeye daisy are eaten in salads in parts of Italy although the plant is not renowned for this use. The root root is said to be edible raw too, preferably in the spring.

Medicinal: The oxeye daisy is mildly aromatic, like its close cousin, chamomile. The leaves and flowers are edible, though palatability may vary. A tea of the plant is useful for relaxing the bronchials.

It is diuretic and astringent, useful for stomach ulcers and bloody piles or urine. Also used as a vaginal douche for cervical ulceration. The daisy is aromatic, used as an antispasmodic for colic and general digestive upset.

Oxeye daisy, harvested before it goes to seed and dried for use later, has been used medicinally for thousands of years in Europe and by the Iroquois, Menominee, Mohegan, Quileute and Shinnecock Native Americans. Internally, the whole plant, particularly the flowers, is said to have successfully helped relax bronchial spasms and whooping coughs.

It has been said to reduce toxicity by stimulating sweat and urination a well as to heal night sweats, wounds, and jaundice, and to effectively heal asthma and nervous conditions.

Even though Ox-eye daisy can be a skin irritant for some, it is said to have been used externally as a lotion to treat ulcers, bruises, cuts and as an eye wash from the flowers to treat conjunctivitis.

Leucanthemum vulgare drawing. We don't know to what extent and in what circumstances it proved effective and a recognised herbalist should be consulted for correct usage and doses.[Montana Plant Life],

Prevention: Oxeye daisy is sometimes an ingredient in wildflower seed mixes, so read labels carefully. Mechanical: dig up the whole plant before it flowers; go 6" down to be sure to get the shallow root systems.

Continue this for a few years, as seeds are in the soil bank. Then reseed: shade oxeye daisy with at least 50% grass or other shady native forb cover to prevent re-establishment.

Grazing: Sheep, goats and horses eat the oxeye daisy, but cows and pigs do not like it. The plant spreads rapidly when cattle pastures are managed with a low stock density and continuous grazing regime. Under these conditions, cows repeatedly select their preferred plants, while ignoring unpalatable species like the oxeye daisy.

Switching to higher stock densities and shorter grazing periods does encourage cattle to eat and trample more of the plant. Intensive grazing and trampling slightly reduces the number of seeds produced, and presumably injures younger rootstalks.

Trampling also brings dormant seeds to the surface and removes the canopy cover so those seeds will germinate with mid-summer rain showers. In normal years, those seedlings will dry-out and die before becoming established, further reducing the number of seeds in the seed bank.

It should be noted, however, that intensive grazing in wet summers may increase the number of successful seedlings. As many as 40% percent of the seeds consumed by cattle may remain viable after passing through the digestive tract, so care should be taken to avoid spreading the seeds when moving stock.

Important: Most "weed problems" are really "people problems" from poor land management and a lack of ecological insight. It is easy to reach for a tool like fire, mowing, or herbicides to attack an out-of-control weed, but often those tools do little to get to the root cause of the weed infestation, and sometimes make the problems worse. Please read more about range ecology, desertification, and invasive weeds on this website before applying any tool of weed control. Go to: Desertification and Invasive Weeds.

https://www.wildflowers-and-weeds.com/weedsinfo/Chrysanthemum_leucanthemum.htm

Many white flowers with yellow centers that commonly grow in lawn grass are daisies. Although daisies themselves are attractive, the plants are usually considered weeds when they pop up in a lawn.

The most common types of lawn daisies are English daisies (Bellis perennis) and oxeye daisies (Chrysanthemum leucanthemum). But you could see other white flowers with yellow centers, include common chickweed (Stellaria media) and white varieties of asters (Aster spp.)

Small English daisies are common in many areas. English daisies grow up to about 8 inches tall but often remain just 3 to 4 inches tall. They bloom from March through September. Their flower petals are white or pinkish, and their green leaves may be either smooth or hairy.

They are common in cool coastal climates and temperate Mediterranean climates, although they are found in nearly all U.S. Department of Agriculture plant hardiness zones. English daisies are listed as an invasive plant on the California Invasive Plant Council Watchlist, so they have the potential to dominate your lawn.

Oxeye daisies grow taller than English daisies. Oxeye daisies are larger than English daisies, reaching heights of up to 3 feet tall. Their flowers are 1 1/2 to 2 inches in diameter, and they have toothed leaves.

Oxeye daisies grow throughout all of the U.S. and most of Canada. They flower from June through August and tend to move into open spaces with their strong roots and rhizomes. Although attractive, these daisies are considered invasive, problematic weeds. When they dieback during the fall, the soil beneath them is exposed, leaving an unsightly bald patch susceptible to erosion.

Other Flower Types - Common chickweed is a low-growing white flower with a yellow center that grows throughout all of the U.S. and Canada. Other flowers with yellow centers and white petals include white nondaisy members of the aster family (Asteraceae). It is also commonly known as the daisy family because most asters have yellow centers.

In general, all types of daisies and weeds are less likely to infest a well-maintained lawn. English daisies like moist areas, so you can prevent them by avoiding overwatering your lawn. They also prefer soils with low nutrient levels, so fertilizing regularly helps prevent English daisies.

Fertilizer also helps lawn grass grow healthily and compete against daisies. To prevent the spread of oxeye daisies, mow the flowers before they have time to produce seeds and spread.

Many gardeners do not mind daisies in the yard and choose not to remove them. You can, however, remove English and oxeye daisies by digging them up.

Because roots left behind in the ground can produce new shoots, dig out the roots as much as possible to prevent the plants from growing back. Postemergent herbicides -- such as those containing triclopyr -- can also help get rid of daisies.

https://homeguides.sfgate.com/white-flowers-yellow-centers-grow-grass-69432.html

When Activision showed the latest Call of Duty: WWII game off to actual World War II veterans, they gave approval on the project's authenticity (which says quite a bit).

Sledgehammer Games has been working for quite some time on making the recently released Call of Duty: WWII as accurate and visceral as possible.

The studio enlisted the help of popular World War II historian and author Martin K.A. Morgan to ensure the game aligned with actual events during the war, and also did tons upon tons of research.

This not only paid off on the consumer front--Call of Duty: WWII made over $500 million in sales in its first 3 days and broke new digital records--but also with actual veterans who served during the tumultuous time.

"We think it's daunting to show our games to our fans, and here we were showing it to people who actually stormed the beaches of Normandy, who actually fought through the Hürtgen Forest and we're showing them those levels from the game," Activision CEO Eric Hirshberg told Newsweek in a recent interview.

"It was an incredibly gratifying experience. After the lights came up, these gentlemen looked at us and said 'yup, you got it right!' It was one of those human moments where something you're making for entertainment purposes intersects with real life in a pretty impactful way."

Hirshberg went on to say that Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare "didn't feel like Call of Duty," and that Sledgehammer Games actually wanted to make a sequel to Advanced Warfare.

Instead, Activision push them towards a more traditional boots-on-the-ground experience with the WWII-based game--something that players and consumers were clamoring for.

Ultimately everything points to Call of Duty: WWII being a landmark success during Activision's important Q3 period. The game has stormed the gates of consoles and PCs worldwide, and will likely continue to do so over the busy holiday season.

https://www.tweaktown.com/news/59794/world-war-ii-veterans-approve-new-call-duty/index.html

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.