Leeks ( tỏi tây / spring onions / scallions ) are in the same onion species as scallions, but they have a different taste and size. They're bigger than scallions, and they also have a mild onion-like flavor.

However, don't go buying leeks now because they might be expensive. Instead, buy them when they're in season, aka in October. The leek is a cultivar of Allium ampeloprasum, the broadleaf wild leek.

The edible part of the plant is a bundle of leaf sheaths that is sometimes erroneously called a stem or stalk. The genus Allium also contains the onion, garlic, shallot, scallion, chive, and Chinese onion.

Saline intrusion - In Soc Trang province, saltwater intrusion and drought have affected more than 2,100ha of rice, up 760ha compared to the end of last month.

Located between the mouths of the Dinh An and Tran De rivers in the Mekong Delta, the district is an islet that is affected by saltwater intrusion in its water bodies and thus lack of water for irrigation in the dry season every year.

Though saltwater intrusion in the Mekong Delta was predicted to come earlier and with higher level of salinity than that recorded in the 2015-2016 dry season, the damages to farming areas are expected to be less serious as authorities and farmers have taken measures to cope with the situation in the 2019-2020 dry season.

Salwater intrusion with a salinity rate of four grammes per litre is expected to enter 50-95 kilometres deep into the delta’s main rivers from February 11-15, an increase of 3-11 kilometres against the same period in 2016, according to the National Centre for Hydro-Meteorology Forecasting.

In Tra Vinh province, saltwater intrusion has entered deep into fields, damaging many rice fields. Do Trung, Director of the Tra Vinh Irrigation Work Exploitation and Management One Member Limited Company, said the company has operated 48 sluices to prevent saltwater intrusion and store fresh water, but saltwater has entered early this year and reached 60-70 km deep into rivers and canals with a salinity rate of 3-10 parts per thousand.

More than 10,000ha of the winter-spring rice in the province face water shortage and 50 percent of the area could be completely damaged, he said. In Soc Trang province, saltwater intrusion and drought have affected more than 2,100ha of rice, up 760ha compared to the end of last month, according to the provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

Lam Hoang Hiep, Vice Chairman of the Soc Trang People’s Committee, said the salinity rate had reached 7-8 parts per thousand in some areas, affecting the lives of locals and agricultural production. The committee has asked the province’s districts to take measures to cope with the situation in each locality, he added.

Nguyen Hoang Hiep, Deputy Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, said in September the ministry asked delta authorities to plant the 2019-2020 winter-spring rice a month earlier than usual to cope with drought and saltwater intrusion.

Before the beginning of the winter-spring crop, authorities in the delta instructed farmers not to grow the winter-spring rice in areas that could be affected by saltwater intrusion. They also urged rice farmers to switch to drought-resistant crops.

The delta was also instructed to reduce the winter-spring rice area to 1.5 million hectares, down 100,000ha against normal years, he said. For fruit cultivation, farmers have built embankments to store irrigation water and have even used huge plastic bags with a capacity of 20-30cu.m each to store irrigation water, he said. “The damage to fruit trees is not expected to be serious,” he said.

The delta’s localities have also added more water pipes to secure the supply of water for locals since September, he said. Tra Vinh province, for instance, has built more than 60km of new water pipes and stored fresh water in reservoirs and canals.

Most households in Tien Giang province which cannot access tap water have water containers with a capacity of 2-3cu.m each to store enough water for drinking and eating during the dry season. The delta, which includes 12 provinces and Can Tho city, is the country’s largest rice, fruit and seafood producer.

In the 2019-2020 dry season, the delta’s provinces and Can Tho began dredging irrigation canals to store fresh water and upgraded and built irrigation systems prior to the beginning of the saltwater intrusion.

Hiep said that construction of many irrigation projects in the delta have been put into use four to 14 months earlier than scheduled. Last month, the delta put into use many irrigation projects that prevent saltwater intrusion and hold fresh water on a farming area of 300,000ha, he said.

As many as 100,000ha of rice and 130,000ha of fruit are expected to be affected by saltwater intrusion and 100,000 households will face a shortage of daily use water. In the 2015-2016 dry season, saltwater intrusion and drought caused the loss of one million tonnes of paddy in the delta, and 500,000 households in the delta suffered a shortage of daily use water./.

https://reliefweb.int/report/viet-nam/mekong-delta-takes-measures-reduce-saltwater-intrusion

It’s mid-season here in Soc Trang Province, Vietnam. The fields are full, and under an easy monsoon wind, the crop rolls like massive emerald sheets. Out here with his rice — that’s where Hai Thach loves to be.

“I so much enjoy working this land,” he says. “Every day, I must visit the land — four to five times a day.” The 63-year-old farmer has been raising rice in this town since he was a boy. His parents did it — his great-grandparents, too. Thach knows his crop.

Rice farmer Hai Thach stands on his farm in Soc Trang Province - “When the rice gets sick, I am sad, too. I feel sad when the rice gets sick,” he says. Squinting out across his acre-and-a-half plot, he reaches down into the sea of green rice plants and snaps off a long yellow leaf.

“The rice now is affected by disease,” he explains. “I expect to lose some of the rice plants — to not be able to harvest them at all.” The bacteria, he says, comes from salt. It’s in the soil and in the water. Saline intrusion is killing rice throughout the region.

Thach stands to lose nearly $300 this crop — close to half of what he takes home in a year. “The conditions are becoming increasingly less favorable for rice,” says Tim Gorman, a doctoral student researching how climate change is impacting the lives of people in the region. “You have a lot of people who are finding it increasingly difficult to grow rice, or to make money growing rice, because of these unfavorable conditions.”

Soc Trang Province, Gorman says, is one of the poorest in the Mekong Delta. The residents rely heavily on rice cultivation. Part of the problem is location. The whole area is veined by channels of the Mekong River. When things are going the rice farmers’ way, a system of canals and gates steers the river’s fresh water to their paddies.

But, just a few miles away is the South China Sea. Being so close to both a large river and the ocean makes this part of the Delta ripe for saline intrusion. “There’s more and more salt water pushing up little streams and distributaries, and also up the main channels of the Mekong River,” Gorman says. “At times — during the dry season, in the winter and spring — it penetrates for dozens of miles inland.”

In a good year, a Delta rice farmer will get three good crops. But with less fresh water around, that’s increasingly hard to do. In 2012, sea water had gone so far inland there wasn’t any fresh water to be found. Thach and his neighbors, their fields full of their third crop of the year, had no good choices.

“If we used no water, the rice would die, and if we use salt water, the rice would also die,” Thach says. “We had to use salty water, and the rice died. We just needed 30 more days, and we would have harvested. But it all died.”

Some of the farmer’s troubles are certainly due to climate change — and those rising sea levels. But maybe nobody should be growing rice here in the first place. “Right now, where we’re standing — we’re standing by this beautiful rice field,” Tim Gorman says. “But 100 years ago, we would have been standing in the middle of basically a swamp.”

It used to be that ocean water would naturally fill this region of the Delta for at least some part of the year. It’s only been in the last half century, Gorman explains, that the Mekong River Delta has become an intensive rice-growing area. First the French, followed by the Americans, started major irrigation projects here.

After its war with the US, Vietnam cleared more mangrove forests and set up even more canals, dykes and gates — converting this region into what’s now known as Vietnam’s rice bowl. In some ways, Gorman says, saline intrusion is nature — with the help of a warming planet — undoing what man has built in the Mekong Delta.

“The part of it with climate change is that the infrastructure designed to protect from direct saline intrusion, from the ocean itself, is increasingly insufficient because the tides are simply higher.”

For now, Gorman says, the state is trying to support the rice sector with protective policies. But Vietnam’s leaders are also weighing just how tenable it is to keep pushing rice in the face of tidal changes like global warming.

In the meantime, what choices do struggling rice farmers have to keep supporting themselves and their families? One option is shrimp farming. About a dozen workers at a Vietnam sorting facility are busy tossing locally-raised shrimp into blue plastic drums. They’re split up by size — from small to enormous.

“Every night, we work from 7 to 10 p.m., and we go through two to eight tons of shrimp every day,” says Hang Thi Dang, who works as a shrimp buyer and seller at the facility. Dang says it used to mostly be a rice town. Now, she’s seeing more and more people get into aquaculture.

“If we can buy and sell shrimp, it’s good for me,” she says with a laugh. Shrimp farming is far riskier than rice, though even a small shrimp operation can earn more than five times what rice farmer Hai Thach brings home in a year. But switching to shrimp isn’t a panacea either — farming shrimp comes with all sorts of its own environmental challenges.

That debate matters not a bit to Thach. He doesn’t have the capital or skill to grow shrimp. He’s 63, his children are gone, and he has grandkids to help look after.

Unlike other frustrated rice growers who are switching to shrimp — or abandoning their farms altogether — Thach is staying put. “I’m too old to leave here, and my land is here, and I will stay here to work on my land and let the young generation leave.” He’ll be here, his feet deep in the monsoon clay, watching the changes.

https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-08-26/rising-sea-levels-mean-trouble-vietnams-rice-farmers

Food security threatened by sea-level rise - Due to sea-level rise, salt water can intrude 30 to 40 kilometres inland, followed by high water levels in the riverbeds and increased sedimentation in canals and flooded plains.

Coastal countries are highly prone to sea-level rise, which leads to salt-water intrusion and increased salinity levels in agricultural land. Also typical for these regions are floods and waterlogging caused by cyclones and typhoons, as well as prolonged drought periods.

All these climate related issues play a major role in rendering agriculture in these areas, rice production in particular, increasingly difficult. Hot spots for climate change impacts - According to the World Bank, salinity issues in Bangladesh will most likely lead to significant shortages of drinking water and irrigation by 2050.

It is also estimated that increased soil salinity, both in coastal and inland areas, may result in a decline in rice yield by 15.6 percent, thus reducing the income of the affected farmers significantly.

The situation is similar in Vietnam where coastal areas are already suffering from sea-level rise and saline intrusion. Vietnam also experiences strong storm surges, rising temperatures and variability in the seasonality of rainfall.

"Due to their extensive coastline and many river deltas, countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam are hot spots for climate change impacts such as sea-level rise and salt water intrusion," says Dr Udaya Sekhar Nagothu from the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research, NIBIO.

Lately, Vietnamese farmers in the Red River and Mekong deltas have been reporting increased salinity levels in their soil and irrigation waters - "High levels of salt in agricultural soil or irrigation water make it difficult for salt sensitive rice plants and other crops to absorb water and necessary nutrients, and as a result, plant growth is suppressed and crop yields significantly reduced."

Call for more salt-tolerant rice varieties - Lately, several farmers in the Mekong and Red River deltas in Vietnam, as well as local authorities, have been reporting increased salinity levels in their soil and irrigation waters. For many, this has caused damage to their properties, as well as loss of livelihoods and income.

Dr Nagothu has coordinated several research projects looking at future climate change impacts on rice production in South and Southeast Asia. He says that more targeted research is needed to address salinity related problems. The development of salt-tolerant rice and crop varieties accessible to smallholder farmers is particularly important.

"As of now, very few seed varieties on the market are able to tolerate the high salt levels that farmers in these regions are experiencing," Dr Nagothu says. "The salt-tolerant rice varieties developed so far are not good enough to meet the high salinity levels. They are also expensive, and thus, unavailable to most smallholder farmers."

Climate-smart agriculture - Trond3: The development of salt-tolerant rice and crop varieties accessible to smallholder farmers is a potential measure to overcome salinity related problems.

In addition to developing new rice varieties, other measures that can be carried out include the implementation of crop rotation systems, soil salinity management using raised seabeds, and changing the date of sowing.

In some regions, a shift from rice production to shrimp cultivation in ponds is being taken up by farmers, as brackish water shrimp tolerates higher salt levels than most rice varieties. Good policy support and capacity building, as well as further investments, are key to develop and put these measures into practice at a larger scale

"To flush out salts from soils in an adequate way, fresh water and a proper drainage system is required," Dr Nagothu says. "Although drainage channels in the saline affected areas do exist in provinces such as Nam Dinh and Soc Trang in Vietnam, the lack of fresh water due to long drought periods actually render them useless."

Improved water and soil management - In the Vietnamese Red River Delta, salt water can intrude 30 to 40 kilometres inland, followed by high water levels in the riverbeds and increased sedimentation in canals and flooded plains.

During the dry season, seawater moves even further inland due to lack of fresh water in the canal. As a result, paddy fields are exposed to high salinity levels in the dry season, making large tracts of productive land unfit for crop cultivation.

The situation in southern Bangladesh is similar, where various measures to meet these issues have been tested. Rice production in Vietnam in the Mekong and Red River deltas is important to the food supply in the country and national economy.

"In Bangladesh, one successful measure has been an aquifier recharge which collects fresh water during the rainy season for use in the dry season. This, in combination with improved soil management, can greatly benefit agricultural land vulnerable to salt water intrusion," Dr Nagothu says.

Through the ClimaViet project, Dr Udaya Sekhar Nagothu and his colleagues have engaged provincial authorities in a series of stakeholder workshops in order to share project results, technology options, capacity building needs and to explore investment alternatives.

Farm testing of salt tolerant rice varieties under different soil and water regimes, training and raising awareness among farmers, as well as developing policy guidelines, have also been important aspects of the project.

According to Dr Nagothu there is a need for an advance in science concerning new rice varieties, alternative cropping systems, physical infrastructure preventing sea-level rise and how to upscale production in line with a growing population.

A more hands-on approach from local policy makers is also necessary. Although they acknowledge the issues at hand, adequate funding is rarely provided for research on the development and upscaling of salinity management measures.

"Developing new seed varieties is expensive. Without sufficient funding, developing more salt tolerant rice and other crop varieties is very difficult," Dr Nagothu says, and adds, "saline levels in soils and irrigation waters in coastal areas are steadily increasing, and it is vital that something is done about it before the situation gets out of hand."

https://phys.org/news/2017-01-food-threatened-sea-level.html

Vài nét về hòn đảo Bidong - Bidong được nhiều du khách Việt quan tâm bởi nét “gần gũi” của nó đối với người Việt. Đây chính là nơi còn lưu lại rất nhiều dấu tích của người những người dân Việt Nam tha hương đến Malaysia giai đoạn từ 1975 - 1992.

Chiếc thuyền chở những người tị nạn lênh đênh trên biển - Cho tới nay, hòn đảo này vẫn còn khá xa lạ với nhiều du khách thập phương và thậm chí là những người dân Malaysia. Vì thế, nó trở thành một sự hiếu kỳ và tò mò của du khách ghé thăm Malaysia.

Mặc dù, những năm gần đây, bảo Bidong trở thành điểm thu hút khách du lịch, nhất là các du khách Việt. Nhưng nhiều người vẫn đặt câu hỏi liệu hòn đảo này tương lai sẽ như thế nào?

Nhiều người nghĩ rằng nơi đây có thể phát triển dịch vụ du lịch với các khu nghỉ dưỡng và những nhà nghỉ cho khách du lịch, nhưng cũng có những suy nghĩ sẽ xây dụng lại nơi này thành điểm du lịch với những tour du lịch lịch sử, khắc họa lại những gì đã diễn ra trong quá khứ.

Câu chuyện về đảo Bidong - Nếu bạn quan tâm đến nét “gần gũi” của đảo Bidong với người dân Việt Nam thì hãy cùng Onetour đến với câu chuyện di dân sau: Sau chiến tranh Việt Nam năm 1975, có hàng nghìn người Việt đã bỏ lại quê hương đầy những tha hóa của chế độ cộng sản mới để ra nước ngoài.

Số lượng người chạy trốn bằng thuyền sang Malaysia ngày càng nhiều. Vào năm 1979 hòn đảo Bidong được cho là nơi đông dân nhất trên trái đất với khoảng 40.000 người tị nạn đông đúc sống trên một khu vực bằng phẳng hầu như không lớn hơn một sân bóng đá.

Hành trình từ Việt Nam sang Malaysia thì rất nguy hiểm mà những con tàu tị nạn lại quá nhỏ hay xảy ra tình trạng quá tải và thường bị cướp biển tấn công. Hàng ngàn người tị nạn đã chết trên biển; hãm hiếp và bắt cóc phụ nữ tị nạn thì vô cùng phổ biến.

Ngoài ra, chính phủ Malaysia và các nước Đông Nam Á khác không khuyến khích những người tị nạn rời bến trên bờ biển của họ. Thuyền tị nạn thường bị đẩy ra nước ngoài hoặc kéo đến Bidong và các trại được chỉ định khác.

Vì vậy, rất nhiều người Việt đã chết không chỉ bị chết do bão tố trên biển mà còn do dịch bệnh, cướp biển, chết vì đói. Đảo Bidong là một hệ quần đảo với 6 đảo nhỏ, trong đó, đảo lớn nhất có diện tích lên đến 260 hecta. Bidong là một hòn đảo đẹp nhưng vẫn còn rất nguyên sơ vào thời điểm người Việt đặt chân đến.

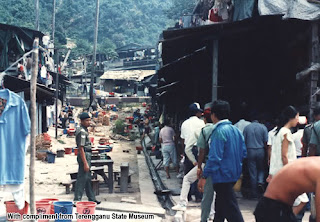

Để đảm bảo cho cuộc sống hiện thời và trong quá trình chờ được di chuyển đến một đất nước mới, nhiều công trình và nhà được xây dựng như nhà ở, trường học, văn phòng, bưu điện, nhà thờ, chùa diền, các tiệm đồ ăn, hay thậm chí cả những sàn nhảy, quán bar, ... đảm bảo đáp ứng các nhu cầu cơ bản.

Dipstick meter for oil check

Tham quan tại đảo Bidong - Những người tỵ nạn cuối cùng rời khỏi nơi đây là năm 1991, nhưng hòn đảo vẫn bị cấm và kiểm soát chặt chẽ trong 8 năm. Cho đến năm 1999, những người du khách đầu tiên mới được đặt chân lên đây.

Một số ngôi nhà ở đây đã bị phá hủy, những đồ dùng và bàn ghế trong văn phòng được làm từ gỗ cũng đã trở nên mục nát, bục gỗ của cầu cũng đã hỏng hoàn toàn.

Chiếc cầu tàu duy nhất phục vụ cho hòn đảo Bidong chỉ có cái nền bằng bê-tông - Nhưng một vài công trình vẫn còn được an toàn như một chiếc thuyền nhân tạo nằm ngay gần một ngôi đền thờ, tưởng nhớ những người đã đến với hòn đảo này, ... như một lời nhắn nhủ thì thầm đến thế giới.

Đến đảo Pulau Bidong, quý khách tham quan các phế tích đã không còn được nguyên vẹn tại đây như chiếc cầu tàu duy nhất phục vụ cho hòn đảo chỉ có cái nền bằng bê-tông.

storm drain

Mộ phần thuyền nhân - một chứng tích lịch sử của người Việt tại Malaysia - Du khách cũng được chứng kiến những tấm biển bằng xi-măng được dựng lên để biểu lộ lòng biết ơn vô tận của Thuyền Nhân đối với Đấng Tối Cao đã giúp họ sống xót qua những chuyến hải hành cũng như đã tưởng niệm những người đã nằm xuống.

cable bridge crossing

Hay đứng trước những bia mộ nơi những người đã nằm xuống trong hành trình vượt biển và cả những người đã qua đời sau khi đặt chân lên hòn đảo để tưởng nhớ về họ. Khung cảnh thiên nhiên đẹp đẽ tại Bidong - Bạn cũng có thể tham quan những công trình nhà ở, chùa phật giáo, nhà thờ công giáo, đài tưởng niệm thuyền nhân, tượng Ông Già Bidong.

Như những dấu ấn của người Việt tha hương những năm 1975 - 1992. Đảo Bidong dưới sự tàn phá của thiên nhiên, những loài động vật sống trên đảo và có thể là con người nên không còn nhiều các dấu tích.

Du khách bơi lội trong làn nước trong và xanh mát của đảo Bidong - Tuy vậy, Bidong cũng là một hòn đảo đẹp và thật sự rất hoang sơ. Nơi đây sẽ là điểm đến thú vị cho những người yêu thiên nhiên và muốn khám phá hệ sinh thái rừng nhiệt đới và đại dương bao lao.

Và tất nhiên, hòn đảo Bidong với bãi biển đẹp hay những trò leo núi, lên suối là những điều bạn không thể bỏ qua. Khám phá đáy đại dương tại hòn đỏa Bidong - Và dù rằng, hòn đảo này chẳng thể nổi tiếng như Redang hay Tioman, nhưng du lịch Malaysia ở nơi đây vẫn thật sự là một phần rất đặc biệt không chỉ trong trái tim người Việt mà cả người Malaysia.

https://onetour.vn/tin-tuc/cam-nang-du-lich-malaysia/nhung-dieu-can-biet-khi-tham-quan-du-lich-bidong.html

The story of these Vietnamese boat people is a sorry tale indeed that must shame many governments. If these boat people did not die at sea, they were attacked by the Thai pirates. If they survived the pirates and death at sea, they were robbed when they reached Malaysia.

And after all that, they faced the risk of being pushed back to sea where they would certainly die in that wide, open, and killer South China Sea. “138 rescued from ‘Malaysia-bound’ boat,” said the Asia News Network today.

The news report went on to say: “The Sri Lankan Navy rescued 138 Bangladeshi and Myanmar nationals on Saturday from a sinking vessel 50 miles off the island’s eastern coast.

Michael Katz (born November 14, 1944) is a former American IFBB professional bodybuilder and former professional football player with the New York Jets, most famous for his appearance with Arnold Schwarzenegger in the 1977 bodybuilding documentary film Pumping Iron.

Of them, 127 are Bangladeshis and the rest are Myanmar nationals, according to a press release of the Sri Lankan Navy. However, in a statement late last night, Bangladesh High Commission in Colombo said most of the survivors are Myanmar nationals.”

“The boat was heading to Malaysia. It ran out of fuel on the way and drifted to Sri Lankan waters. According to a Sri Lankan newspaper, citizens of the country pay as much as $3,000 to travel across the sea.” (Read more here).

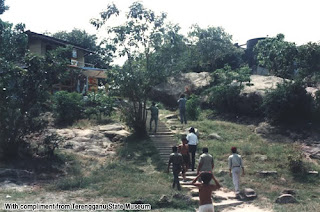

The news report above reminds me of my early days in Terengganu. I lived there for 20 years from 1974 to 1994. This was soon after the fall of Saigon in 1975 when we woke up one morning and found a boat beached along Batu Burok in Kuala Terengganu. It was a boatload of Vietnamese.

THE FALL OF SAIGON: 1975 - From that day on the boats kept coming, sometimes more than one a day. And they came mostly during the year-end monsoon when most boats that size would stay in port due to the strong winds and treacherous seas.

But they chose this particular time so that the wind could blow their boats to Terengganu. This ensured that they reached Terengganu, and in a faster time as well, plus they could avoid drifting into the Gulf of Thailand where they would be prey to the Thai pirates (who were fishermen and Thai navy/marines moonlighting as pirates).

The story of these Vietnamese boat people is a sorry tale indeed that must shame many governments. If these boat people did not die at sea, they were attacked by the Thai pirates. If they survived the pirates and death at sea, they were robbed when they reached Malaysia.

And after all that, they faced the risk of being pushed back to sea where they would certainly die in that wide, open, and killer South China Sea - They soon learned to puncture their boats just before they touched land and then swim the rest of the way so that they cannot be pushed back to sea.

But the undercurrents of the South China Sea along Terengganu were treacherous, especially during the monsoon period. You would get swept out to sea and drown unless you were a strong swimmer. And most of the boat people were very weak and near collapse.

Hence many drowned. Even one Olympic swimmer medallist who was snorkelling in Terengganu drowned once. And he was an Olympic medallist, mind you. Elizabeth Becker, who wrote ‘When the War Was Over, 1986’, cites the UN High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) statistics as 250,000 boat people died at sea while 929,600 reached asylum.

Rummel, however, says that 500,000 Vietnamese boat people died. It is estimated that for every two who reached dry land one died trying. Trying to reach land was one issue. It is after they reached land was when the real nightmare started, as if the journey itself was not a nightmare enough. Then we realise how cruel humans can be to fellow humans.

SWIM OR DIE - The early group that came in the mid- to late-1970s were mainly Vietnamese who had worked for the South Vietnamese government (some of them in the secret police and hit squads — even one colonel in the army who had murdered many VCs). In fact, one boat was a boatload of soldiers in uniform armed with M16s and rocket launchers.

This early group could be considered as political refugees, those who would be punished and/or killed if they remained in Vietnam. The later group were mainly economic refugees.

These were people who had money and just wanted to leave and migrate to the west for a better future. They only wanted to go to a ‘white’ country. They refused to stay in Thailand or Malaysia.

This second group had money. And they paid an expensive bribe to be allowed to leave Vietnam — just like what the Jews had to do to leave Nazi controlled Europe during the Second World War. And many in this second group were Chinese.

They had stacks of US Dollars, gold and diamonds on them. Hence everyone wanted to rob them — the Thais, the Malaysians, the army, the navy, the fishermen, the pirates, the civilians, the shopkeepers who sold them bread and Maggi Mee at 10 or 20 times the normal price, and the middlemen who helped exchange their US Dollars, gold and diamonds for Malaysian Ringgit.

I did buy some of the diamonds after they had been verified as real diamonds and not fakes. I am still in possession of some of them until today, those I bought 35 years or so ago back in the 1970s/1980s.

Looking back now, these Vietnamese boat people were given a raw deal. The early batch of Vietnamese boat people was not so badly treated. They were real refugees and mostly poor. It is the later batch of rich Chinese who brought in loads of cash, gold and diamonds that suffered.

In the beginning, the west was quite happy to take these refugees. Later, because these refugees were not considered real refugees but economic refugees, the west was not so quick to absorb them. So they were left to the mercy of the vultures that stripped them clean.

Anyway, this article has nothing to do with the RCI hearing going on in Sabah. It is just that talk of refugees brought back memories of Terengganu of the 1970s and 1980s when we would wake up every morning and find boats with Vietnamese who had arrived in the middle of the night waiting to be screwed — both literally and figure of speech.

The Malays have a saying for this: sudah jatuh ditimpa tangga. This means after you fall down the ladder falls on you — what the English would say: being kicked in the teeth after you are down.

The ‘Boat People of Vietnam’ seemed to encapsulate all the suffering Vietnam had suffered from 1965 to 1975. Despite the end of the Vietnam War, tragedy for the people of Vietnam continued into 1978-79.

The term ‘Boat People’ not only applies to the refugees who fled Vietnam but also to the people of Cambodia and Laos who did the same but tend to come under the same umbrella term. The term ‘Vietnamese Boat People’ tends to be associated with only those in the former South who fled the new Communist government.

However, people in what was North Vietnam who had an ethnic Chinese background fled to Hong Kong at the same time fearing some form of retribution from the government in Hanoi.

In late 1978, Indo-China degenerated into wholesale confrontation and war between Vietnam and Kampuchea (Cambodia) and China. In December 1978, Vietnam attacked Kampuchea while in February 1979, Vietnam attacked Chinese forces in the north. These two conflicts produced a huge number of refugees.

Many in what was South Vietnam feared the rule of their communist masters from what had been North Vietnam. Despite the creation of a united Republic of Vietnam in 1975, many in the South feared retribution once it was found out that they had fought against the North during the actual war.

The rule exerted in Ho Chi Minh City (formally Saigon) was repressive as this was seen as a bastion of ‘Americanisation’. Traditional freedoms were few. It has been estimated that 65,000 Vietnamese were executed after the end of the war with 1 million being sent to prison/re-education camps where an estimated 165,000 died. Many took the drastic decision to leave the country – an illegal act under the communis government.

As an air flight out of Vietnam was out of the question, many took to makeshift boats in an effort to flee to start a new life elsewhere. Alternately, fishing boats were utilised.

While perfectly safe for near-shore fishing, they were not built for the open waters. This was coupled with the fact that they were usually chronically overcrowded, thus making any journey into the open seas potentially highly dangerous.

No one can be sure how many people took the decision to flee, nor are there any definitive casualty figures. However, the number who attempted to flee has been put as high as 1.5 million. Estimates for deaths vary from 50,000 to 200,000 (Australian Immigration Ministry).

The primary cause of death was drowning though many refugees were attacked by pirates and murdered or sold into slavery and prostitution. Some countries in the region, such as Malaya, turned the boat people away even if they did manage to land.

Boats carrying the refugees were deliberately sunk offshore by those in them to stop the authorities towing them back out to sea. Many of these refugees ended up settling in the United States and Europe. The United States accepted 823,000 refugees; Britain accepted 19,000; France accepted 96,000; Australia and Canada accepted 137,000 each.

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/vietnam_boat_people.htm

The boat people of Pulau Bidong - (Sin Chew, 6 Oct 2012) – The federal government decided in 1978 to borrow Pulau Bidong from the Terengganu state government to temporarily house the increasing number of boat people arriving in the country.

From that year on, Pulau Bidong was isolated from the rest of Peninsular Malaysia and outsiders were barred from visiting the island. Similarly, these boat people were also prohibited from leaving the island while waiting for a third country to pick them up.

During its peak Pulau Bidong accommodated as many as 250,000 boat people, who were gradually sent to third countries in batches. At the same time, the Malaysian government was also under mounting pressure from the fishermen in Terengganu.

For many fishermen, Pulau Bidong has indeed been a safe haven for generations. Even with the massive storms in South China Sea, this tiny island remains the fishermen’s safest refuge.

However, the island became out of bound to the fishermen ever since the government started housing boat people there for over a decade. The irate fishermen rose up in protest.

After the Terengganu state government assured the fishermen, the federal government finally announced on March 14, 1989 a deadline for the boat people to leave, and return the island to Terengganu.

Nevertheless, the number of boat people flooding into the east coast of Malaysia continued to rise, averaging 65 people a day and forcing the government to defer closing the refugee camp.

On November 30, 1991, Pulau Bidong was finally closed down by the federal government, with then Deputy Prime Minister Tun Ghafar Baba returning the island to the Terengganu state government on behalf of the federal government.

Prior to the closure of the Pulau Bidong refugee camp in 1991, the remaining 12,000 boat people on the island were transferred to the refugee camp outside KL awaiting repatriation to Vietnam. The training centre and other facilities constructed at a cost of RM170 million with UNHCR funds were all handed over to Terengganu.

While they were here, the boat people called the island the “Island of Sorrows,” as though they wanted to leave all their grievances behind on this island. As the Vietnamese government celebrated the 30th anniversary of Liberation, 142 former boat people from around the world returned to Pulau Bidong to pay respect to their late relatives and compatriots.

These Vietnamese, now living in third countries, were youngsters in their twenties when they left their homeland in search of freedom and better life. They now returned to the island as middle-aged people in their fifties and sixties.

This transitional “home” of theirs has changed completely and many of the buildings on the island have gone into disrepair following years of abandonment and neglect, as the graves of their bereaved relatives and friends are now run over by overgrowth.

During the visit of these former boat people, they erected a concrete monument with the following inscriptions: Front: “In remembrance of millions of Vietnamese boat people who sacrificed their lives in search of freedom (1975-1996).

Eternal peace be with those suffering from starvation, thirst, violence, physical exhaustion and all causes of death. Their sacrifices will be remembered forever — Overseas Vietnamese boat people community, erected 2005.”

Rear: “Our heartfelt thanks to the UNHCR, the Red Cross Society, the Malaysian Red Crescent Society and other relief organisations from around the world, the Malaysian government and all Malaysians who offered us their most valued assistance. We also wish to thank thousands of volunteers who once helped the boat people — Overseas Vietnamese boat people community, erected 2005.”

https://www.malaysia-today.net/2013/02/04/sudah-jatuh-ditimpa-tangga/

Gia Long (Vietnamese: [zaː lawŋm]; 8 February 1762 – 3 February 1820), born Nguyễn Phúc Ánh or Nguyễn Ánh,[b] was the first Emperor of the Nguyễn dynasty of Vietnam. Unifying what is now modern Vietnam in 1802, he founded the Nguyễn dynasty, the last of the Vietnamese dynasties.

A nephew of the last Nguyễn lord who ruled over southern Vietnam, Nguyễn Ánh was forced into hiding in 1777 as a fifteen-year-old when his family was slain in the Tây Sơn revolt. After several changes of fortune in which his loyalists regained and again lost Saigon, he befriended the French Catholic priest Pigneau de Behaine.

Pigneau championed his cause to the French government and managed to recruit volunteers when that fell through to help Nguyễn Ánh regain the throne. From 1789, Nguyễn Ánh was once again in the ascendancy and began his northward march to defeat the Tây Sơn, reaching the border with China by 1802, which had previously been under the control of the Trịnh lords.

Following their defeat, he succeeded in reuniting Vietnam after centuries of internecine feudal warfare, with a greater land mass than ever before, stretching from China down to the Gulf of Siam.

Gia Long's rule was noted for its Confucian orthodoxy. He overcame the Tây Sơn rebellion and reinstated the classical Confucian education and civil service system.

He moved the capital from Hanoi south to Huế as the country's populace had also shifted south over the preceding centuries, and built up fortresses and a palace in his new capital. Using French expertise, he modernized Vietnam's defensive capabilities. In deference to the assistance of his French friends, he tolerated the activities of Roman Catholic missionaries, something that became increasingly restricted under his successors.

Under his rule, Vietnam strengthened its military dominance in Indochina, expelling Siamese forces from Cambodia and turning it into a vassal state. Born on 8 February 1762,[3] he also had two other names in his childhood: Nguyễn Phúc Chủng (阮福種) and Nguyễn Phúc Noãn (阮福暖).

Nguyễn Ánh was the third son of Nguyễn Phúc Luân and Nguyễn Thị Hoàn. Luan was the second son of Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát of southern Vietnam; the first son had already predeceased the incumbent Lord.

There are differing accounts on which son was the designated successor. According to one theory, Luân was the designated heir, but a high-ranking mandarin named Trương Phúc Loan changed Khoat's will of succession on his deathbed, and installed Luan's younger brother Nguyễn Phúc Thuần, the sixteenth son, the throne in 1765.

Luan was jailed and died in the 1765, the same year as Thuan's installation. However, the historian Choi Byung Wook claims that the notion that Luân was the designated heir was based on fact but was propagated by 19th century Nguyễn Dynasty historians after Nguyễn Ánh had taken the throne as Gia Long to establish the emperor's legitimacy.

According to Choi, Lord Khoát had originally chosen the ninth son, who then died, leaving Loan to install Lord Thuần. At the time, the alternative was the eldest son of the ninth son, Nguyễn Phúc Dương, whom opposition groups later tried unsuccessfully to convince to join them as a figurehead to lend legitimacy.

In 1775, Thuan was forced to share power with Dương by military leaders who supported the Nguyêns. At this time, Nguyễn Ánh was a minor member of the family and did not have any political support among court powerbrokers.

However, Thuan lost his position as lord of southern Vietnam and was killed, along with Duong, during the Tây Sơn rebellion led by the brothers Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Huệ and Nguyễn Lữ in 1777.

Nguyễn Ánh was the most senior member of the ruling family to have survived the Tây Sơn victory, which pushed the Nguyễn from their heartland in central Vietnam, southwards towards Saigon and into the Mekong Delta region in the far south.

This turn of events changed the nature of the Nguyễn power hierarchy; the family and the first leader Nguyễn Hoàng had originally come from Thanh Hoa Province in northern Vietnam, and this is where most of their senior military and civil leadership's heritage derived from, but as a result of the Tây Sơn's initial successes.

Much of this old power base was destroyed and Nguyễn Ánh had to rebuild his support network among southerners, who later became the core of the regime when the Nguyễn Dynasty was established.

Nguyễn Ánh was sheltered by a Catholic priest Paul Nghi (Phaolô Hồ Văn Nghị) in Rạch Giá. Later, he fled to Hà Tiên on the southern coastal tip of Vietnam, where he met Pigneau de Behaine, a French priest who became his adviser and played a major part in his rise to power.

Receiving information from Paul Nghi, Pigneau avoided the Tay Son army in Cambodia, and came back to assist Nguyễn Ánh. They hid in the forest to avoid the pursuit of Tay Son army. Together, they escaped to the island of Pulo Panjang in the Gulf of Siam.

Pigneau hoped that by playing a substantial role in a Nguyễn Ánh victory, he would be in position to lever important concessions for the Catholic Church in Vietnam, helping its expansion in Southeast Asia. Pigneau de Behaine, the French priest who recruited armies for Nguyễn Ánh during the war against the Tây Sơn.

In late 1777, the main part of the Tây Sơn army left Saigon to go north and attack the Trịnh lords, who ruled the other half of Vietnam. Nguyễn Ánh stealthily returned to the mainland, rejoining his supporters and reclaimed the city of Saigon.

He was crucially aided by the efforts of Do Thanh Nhon, a senior Nguyễn Lord commander who had organized an army for him, which was supplemented by Cambodian mercenaries and Chinese pirates.

The following year, Nhon expelled additional Tây Sơn troops from the surrounding province of Gia Dinh and inflicted heavy losses on the Tây Sơn naval fleet. Taking advantage of the more favorable situation, Nguyễn Ánh sent a diplomatic mission to Siam to propose a treaty of friendship.

This potential pact, however, was derailed in 1779 when the Cambodians rose up against their pro-Siamese leader Ang Non II. Nguyễn Ánh sent Nhon to assist the revolt, which eventually saw Ang Non II defeated decisively and executed.

Nhon returned to Saigon with high honor and concentrated his efforts on improving the Nguyễn navy. In 1780, in an attempt to strengthen his political status, Nguyễn Ánh proclaimed himself Nguyễn vương (Nguyễn king or Nguyễn ruler in Vietnamese) with the support of Nhon's Dông Sơn Army.

In 1781, Nguyễn Ánh sent further forces to prop up the Cambodian regime against Siamese armies who wanted to reassert their control. Shortly thereafter, Nguyễn Ánh had Nhon brutally murdered. The reason remains unclear, but it was postulated that he did so because Nhon's fame and military success was overshadowing him. At the time, Nhon had much, if not dominant power, behind the scenes.

According to later Nguyễn Dynasty chronicles, Nhon's powers included that of deciding who would receive the death penalty, and allocating budget expenditures. Nhon also refused to allocate money for royal spending. Nhon and his men were also reported to have acted in an abrasive and disrespectful manner to Nguyễn Ánh.

The Tây Sơn brothers reportedly broke out in celebration upon hearing of Nhon's execution, as Nhon was the Nguyễn officer that they feared the most. Large parts of Nhon's supporters rebelled, weakening the Nguyễn army, and within a few months, the Tây Sơn had recaptured Saigon mainly on the back of naval barrages.

Nguyễn Ánh was forced to flee to Ha Tien, and then onto the island of Phu Quoc. Meanwhile, some of his forces continued to resist in his absence. While the murder of Nhon weakened Nguyễn Ánh in the short term, as many southerners who were personally loyal to Nhon broke away and counter-attacked.

It also allowed Nguyễn Ánh to gain autonomy and then take steps towards exerted direct control over the remaining local forces of the Dong Son who were willing to work with him. Nguyễn Ánh also benefited from the support of Chau Van Tiep, who had a power base in the central highlands between the strongholds of the Nguyễn and the Tây Sơn.

In October 1782, the tide shifted again, when forces led by Nguyễn Phúc Mân, Nguyễn Ánh's younger brother, and Chau Van Tiep drove the Tây Sơn out of Saigon. Nguyễn Ánh returned to Saigon, as did Pigneau.

The hold was tenuous, and a counterattack by the Tây Sơn in early 1783 saw a heavy defeat to the Nguyễn, with Nguyen Man killed in battle. Nguyễn Ánh again fled to Phu Quoc, but this time his hiding place was discovered. He managed to escape the pursuing Tây Sơn fleet to Koh-rong island in the Bay of Kompongsom.

Again, his hideout was discovered and encircled by the rebel fleet. However, a typhoon hit the area, and he managed to break the naval siege and escape to another island amid the confusion. In early-1784, Nguyễn Ánh went to seek Siamese aid, which was forthcoming, but the extra 20,000 men failed to weaken the Tây Sơn's hold on power.

This forced Nguyễn Ánh to become a refugee in Siam in 1785. To make matters worse, the Tây Sơn regularly raided the rice growing areas of the south during the harvesting season, depriving the Nguyễn of their food supply.

Nguyễn Ánh eventually came to the conclusion that using Siamese military aid would generate a backlash amongst the populace, due to prevailing Vietnamese hostility towards Siam.

Deflated by his situation, Nguyễn Ánh asked Pigneau to appeal for French aid, and allowed Pigneau to take his son Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh with him as a sign of good faith. This came about after Nguyễn Ánh had considered enlisting English, Dutch, Portuguese and Spanish assistance.

Pigneau advised against Nguyễn Ánh's original plan to seek Dutch aid from Batavia, fearing that the support of the Protestant Dutch would hinder the advancement of Catholicism. Pigneau left Vietnam in December, arriving in Pondicherry, India in February 1785 with Nguyễn Ánh's royal seal.

Nguyễn Ánh had authorized him to make concessions to France in return for military assistance. The French administration in Pondicherry, led by acting governor Coutenceau des Algrains, was conservative in outlook and resolutely opposed intervention in southern Vietnam.

To compound the already complex situation, Pigneau was denounced by Spanish Franciscans in the Vatican, and he sought to transfer his political mandate to Portuguese forces. The Portuguese had earlier offered Nguyễn Ánh 56 ships to use against the Tây Sơn.

In July 1786, after more than 12 months of fruitless lobbying in Pondicherry, Governor de Cossigny allowed Pigneau to travel back to France to directly ask the royal court for assistance. Arriving at the court of Louis XVI in Versailles in February 1787, Pigneau had difficulty in gathering support for a French expedition in support of Nguyễn Ánh.

This was due to the parlous financial state of the country prior to the French Revolution. Pigneau was helped by Pierre Poivre, who had previously been involved in seeking French commercial interests in Vietnam.

Pigneau told the court that if France invested in Nguyễn Ánh and acquired a few fortified positions on the Vietnamese coast in return, then they would have the capability to "dominate the seas of China and of the archipelago", and with it, control of Asian commerce.

In November 1787, a treaty of alliance was concluded between France and Cochinchina, the European term for southern Vietnam, in Nguyễn Ánh's name. Pigneau signed the treaty as the "Royal Commissioner of France for Cochinchina".

France promised four frigates, 1,650 fully equipped French soldiers and 250 Indian sepoys in return for the cession of Pulo Condore and Tourane (Da Nang), as well as tree trade to the exclusion of all other countries.

However, the freedom to spread Christianity was not included. However, Pigneau found that Governor Thomas Conway of Pondicherry was unwilling to fulfill the agreement; Conway had been instructed by Paris to determine when to organize the aid, if at all.

Pigneau was thus forced to use funds raised in France to enlist French volunteers and mercenaries. He also managed to procure several shipments of arms and munitions from Mauritius and Pondicherry.

A painting of Nguyễn Ánh in audience with King Rama I in Phra Thinang Amarin Winitchai, Bangkok, 1782 - Meanwhile, the Royal Court of Siam in Bangkok,[d] under King Rama I,[e] warmly welcomed Nguyễn Ánh.

The Vietnamese refugees were allowed to built a small village between Samsen and Bangpho, and named it Long-kỳ (Thai: Lat Tonpho). Ánh had stayed in Siam with a contingent of troops until August 1787.

His soldiers served in Siam's war against Bodawpaya of Burma (1785–86). On 18 December 1786, Nguyễn Ánh signed a treaty of alliance with the Portuguese in Bangkok. In the next year, António (An Tôn Lỗi), a Portuguese from Goa, came to Bangkok, brought Western soldiers and warships to Ánh.

This disgusted the Siamese and Ánh had to refuse the aid from Portuguese. After this incident, Ánh was no longer trusted by the Siamese. Having consolidated their hold on southern Vietnam, the Tây Sơn decided to move north to unify the country. However, the withdrawal of troops from the Gia Dinh garrison weakened them their hold on the south.

This was compounded by reports that Nguyễn Nhạc was being attacked near Qui Nhơn by his own brother Nguyễn Huệ, and that more Tây Sơn troops were being evacuated from Gia Dinh by their commander Dang Van Tran in order to aid Nguyễn Nhạc.

Sensing Tây Sơn vulnerability in the south, Nguyễn Ánh assembled his forces at home and abroad in preparation for an immediate offensive. Ánh secretly left Siam in the night, leaving a letter in his house, he decided to head for southern Vietnam by boat.

Vietnamese refugees were preparing to leave, people nearby heard about this and told it to Phraya Phrakhlang. Phraya Phrakhlang reported it to King Rama I and the Front Palace Maha Sura Singhanat. Sura Singhanat was extremely angry, he chased them personally. At dawn, Sura Singhanat saw Ánh's boat at the mouth of the bay.

Finally, Vietnamese escaped successfully. Ánh arrived at Hà Tiên then to Long Xuyên (Cà Mau), but he failed in his first attempt to recapture Gia Dinh, having failed to convince the local warlord in the Mekong Delta, Vo Tanh to join his assault.

The following year, Nguyễn Ánh managed to persuade Tanh to join in, having given his sister to the warlord as a concubine. He eventually succeeded in taking Mỹ Tho, made it the main staging point for his operations, and rebuilt his army. After a hard-fought battle, his soldiers captured Saigon on 7 September 1788.

Eventually, Pigneau assembled four vessels to sail to Vietnam from Pondicherry, arriving in Saigon on 24 July 1789. The combined forces helped to consolidate Nguyễn Ánh's hold on southern Vietnam.

The exact magnitude of foreign aid and the importance of their contribution to Gia Long's success is a point of dispute. Earlier scholars asserted that up to 400 Frenchmen enlisted, but more recent work has claimed that less than 100 soldiers were present, along with approximately a dozen officers.

After more than a decade of battle, Nguyễn Ánh had finally managed to gain control of Saigon for long enough to have time to start a permanent base in area, and prepare to build up for a decisive power struggle with the Tây Sơn.

The area around Saigon, known as Gia Dinh, began to be referred to as its own region, because Nguyễn Ánh's presence was becoming entrenched, distinguishing and associating the area with a political base. Nguyễn Ánh's military was able to settle down there, and a civil service was reestablished.

According to the historian Keith Taylor, this was the first time that the southern third of Vietnam was integrated "as a region capable of participating successfully in war and politics among Vietnamese speakers", which could "compete for ascendancy with all the other places inhabited by speakers of the Vietnamese language".

A Council of High Officials consisting of military and civil officials was created in 1788, as was a tax collection system. In the same year, regulations were passed to force half the male population of Gia Dinh to serve as conscripts, and two years later, a system of military colonies was started bolster the Nguyễn support base across all racial groups, including ethnic Khmers and Chinese.

The French officers enlisted by Pigneau helped to train Nguyễn Ánh's armed forces and introduced Western technological expertise to the war effort. The navy was trained by Jean-Marie Dayot,[49] who supervised the construction of bronze-plated naval vessels.

Olivier de Puymanel was responsible for training the army and the construction of fortifications. He taught the troops various methods of manufacturing and using European-style artillery and introduced European infantry formations and tactics.

Pigneau and other missionaries acted as business agents for Nguyễn Ánh, purchasing munitions and other military supplies. Pigneau also served as an advisor and de facto foreign minister until his death in 1799.

Upon Pigneau's death, Gia Long's funeral oration described the Frenchman as "the most illustrious foreigner ever to appear at the court of Cochinchina". Pigneau was buried in the presence of the crown prince, all mandarins of the court, the royal bodyguard of 12,000 men and 40,000 mourners.

Following the recapture of Saigon, Nguyễn Ánh consolidated his power base and prepared the destruction of the Tây Sơn. His enemies had regularly raided the south and confiscated the annual rice harvests, so Nguyễn Ánh was keen to strengthen his defense.

One of Nguyễn Ánh's first actions was to ask the French officers to design and supervise the construction of a modern European-style citadel in Saigon. The citadel was designed by Theodore Lebrun and de Puymanel, with 30,000 people mobilized for its construction in 1790.

The townfolk and their mandarins were punitively taxed for the work, the laborers were worked so hard that they revolted. When finished, the stone citadel had a perimeter measuring 4,176 meters in a Vauban model. The fortress was bordered on three sides by pre-existing waterways, bolstering its natural defensive capability.

Following the construction of the citadel, the Tây Sơn never again attempted to sail down the Saigon River and try to recapture the city, its presence having endowed Nguyễn Ánh with a substantial psychological advantage over his opponents.

Nguyễn Ánh took a keen personal interest in fortifications, ordering his French advisors to travel home and bring back books with the latest scientific and technical studies on the subject. The Nguyễn royal palace was built inside the citadel.

Agrarian Reform and Economic Growth - With the southern region secured, Nguyễn Ánh turned his attention to agrarian reforms. Due to Tây Sơn naval raids on the rice crop via inland waterways, the area suffered chronic rice shortages.

Although the land was extremely fertile, the region was agriculturally underexploited, having been occupied by Vietnamese settlers only relatively recently. Furthermore, agricultural activities had also been significantly curtailed during the extended warfare with the Tây Sơn.

Nguyễn Ánh's agricultural reforms were based around extending to the south a traditional form of agrarian expansion, the đồn điền, which roughly translates as "military settlement" or "military holding", the emphasis being on the military origin of this form of colonization.

These were first used during the 15th century reign of Lê Thánh Tông in the southward expansion of Vietnam. The central government supplied military units with agricultural tools and grain for nourishment and planting.

The soldiers were then assigned land to defend, clear and cultivate, and had to pay some of their harvest as tax. In the past, a military presence was required because the land was being seized from the conquered indigenous population. Under Nguyễn Ánh's rule, pacification was not usually needed but the basic model remained intact.

Settlers were granted fallow land, given agricultural equipment, work animals and grain. After several years, they were required to pay grain tax. The program greatly reduced the amount of idle, uncultivated land. Large surpluses of grain, taxable by the state, resulted.

By 1800, the increased agricultural productivity had allowed Nguyễn Ánh to support a sizeable army of more than 30,000 soldiers and a navy of more than 1,200 vessels.

The surplus from the state granary was sold to European and Asian traders to facilitate the importation of raw materials for military purposes, in particular iron, bronze, and sulfur.

The government also purchased castor sugar from local farmers and traded it for weapons from European manufacturers. The food surplus allowed Nguyễn Ánh to engage in welfare initiatives that improved morale and loyalty among his subjects, thereby increasing his support base.

The surplus grain was deposited in granaries built along the northward route out of Saigon, following the advance of the Nguyễn army into Tây Sơn territory. This allowed his troops to be fed from southern supplies, rather than eating from the areas that he was attempting to conquer or win over.

Newly acquired regions were given tax exemptions, and surrendered Tây Sơn mandarins were appointed to equivalent positions with the same salaries in the Nguyễn administration. The French Navy officer Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau served Emperor Gia Long.

Nguyễn Ánh used his new Chu Su Naval workshop to improve his inferior navy, which was much smaller than the Tây Sơn fleet and hitherto unable to prevent their rice raids.

Nguyễn Ánh had first attempted to acquire modern naval vessels in 1781, when on the advice of Pigneau, he had chartered Portuguese vessels of European design, complete with crew and artillery.

This initial experience proved to be disastrous. For reasons that remain unclear, two of the vessels fled in the midst of battle against the Tây Sơn, while angry Vietnamese soldiers killed the third crew. In 1789, Pigneau returned to Vietnam from Pondicherry with two vessels, which stayed in the Nguyễn service long-term.

Over time, Vietnamese sailors replaced the original French and Indian crew under the command of French officers. These vessels became the foundation for an expanded military and merchant Nguyen naval force, with Nguyễn Ánh chartering and purchasing more European vessels to reinforce Vietnamese-built ships.

However, traditional Vietnamese-style galleys and small sailing ships remained the majority of the fleet. By 1794, two European vessels were operating together with 200 Vietnamese boats against the Tây Sơn near Qui Nhơn.

In 1799, a British trader by the name of Berry reported that the Nguyễn fleet had departed Saigon along the Saigon River with 100 galleys, 40 junks, 200 smaller boats and 800 carriers, accompanied by three European sloops.

In 1801, one naval division was reported to have included nine European vessels armed with 60 guns, five vessels with 50 guns, 40 with 16 guns, 100 junks, 119 galleys and 365 smaller boats. Most of the European-style vessels were built in the shipyard that Nguyễn Ánh had commissioned in Saigon.

He took a deep personal interest in the naval program, directly supervising the work and spending several hours a day dockside. One witness noted "One principal tendency of his ambition is to naval science, as a proof of this he has been heard to say he would build ships of the line on the European plan."

By 1792, fifteen frigates were under construction, with a design that mixed Chinese and European specifications, equipped with 14 guns.

The Vietnamese learned European naval architecture by dismantling an old European vessel into its components, so that Vietnamese shipbuilders could understand the separate facets of European shipbuilding, before reassembling it.

They then applied their newfound knowledge to create replicas of the boats. Nguyễn Ánh studied naval carpentry techniques and was said to be adept at it, and learned navigational theory from the French books that Pigneau translated, particularly Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert's Encyclopédie. The Saigon shipyard was widely praised by European travelers.

Despite his extensive reliance on French officers on matters of military technology, Nguyễn Ánh limited his inner military circle to Vietnamese.

The Frenchmen decried his refusal to take their tactical advice. Chaigneau reported that the Europeans continually urged Nguyễn Ánh to take the initiative and launch bold attacks against Tây Sơn installations.

Nguyễn Ánh refused, preferring to proceed slowly, consolidating his gains in one area and strengthening his economic and military base, before attacking another. In the first four years after establishing himself in Saigon in 1788, Nguyễn Ánh focused on tightening his grip on the Gia Dinh area and its productive rice paddies.

Although his forces exerted a degree on control over areas to the north such as Khanh Hoa, Phu Yen and Binh Thuan, their main presence in the northern areas were mainly through naval forces and not concentrated on land occupation.

This was because those areas were not very fertile in terms of growing rice and often affected by famines, and occupying the land would have meant an obligation to feed the populace, putting a strain on resources.

During this four-year period, Nguyễn Ánh sent missions to Siam, Cambodia and south to the Straits of Malacca and purchase more European military equipment. Over time, Nguyễn Ánh gradually reduced the military role of his French allies on the battlefield.

In the naval battle at Thi Nai in 1792, Dayot led the Nguyễn naval attack, but by 1801, a seaborne offensive in the same area was led by the Nguyen Van Truong, Vo Duy Nguy and Lê Văn Duyệt, with Chaigneau, Vannier, and de Forsans in supporting positions.

The infantry attack on Qui Nhơn in 1793 was conducted, according to Nguyen historiography, in cooperation with "Western soldiers". The same source recorded that by 1801, Nguyen operations in the same area were directed by Vietnamese generals, whereas Chaigneau and Vannier were responsible for organizing supply lines.

Vietnamese "Tirailleur" soldiers of the Nguyễn dynasty - In 1792, the middle and the most notable of the three Tây Sơn brothers, Nguyễn Huệ Quang Trung, who had gained recognition as Emperor of Vietnam by driving the Lê dynasty and China out of northern Vietnam, died suddenly.

Nguyễn Ánh took advantage of the situation and attacked northwards. By now, the majority of the original French soldiers, whose number peaked at less than 80 by some estimates, had departed.

The majority of the fighting occurred in and around the coastal towns of Nha Trang in central Vietnam and Qui Nhơn further to the north in Bình Định Province, the birthplace and stronghold of the Tây Sơn.

Nguyễn Ánh began by deploying his expanded and modernised naval fleet in raids against coastal Tây Sơn territory. His fleet left Saigon and sailed northward on an annual basis during June and July, carried by southwesterly winds.

The naval offensives were reinforced by infantry campaigns. His fleet would then return south when the monsoon ended, on the back of northeasterly winds. The large European wind-powered vessels gave the Nguyễn navy a commanding artillery advantage, as they had a superior range to the Tây Sơn cannons on the coast.

Combined with traditional galleys and a crew that was highly regarded for its discipline, skill and bravery, the European-style vessels in the Nguyễn fleet inflicted hundreds of losses against the Tây Sơn in 1792 and 1793.

In 1794, after a successful campaign in the Nha Trang region, Nguyễn Ánh ordered de Puymanel to build a citadel at Duyen Khanh, near the city, instead of retreating south with the seasonal northeasterly breeze.

A Nguyen garrison was established there under the command of Nguyễn Ánh's eldest son and heir, Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh, assisted by Pigneau and de Puymanel. The Tây Sơn laid siege to Duyen Khanh in May 1794, but Nguyen forces were able to keep them out.

Shortly after the siege ended, reinforcements arrived from Saigon and offensive operations against the Tây Sơn duly resumed. The campaign was the first time that the Nguyễn were able to operate in Tây Sơn heartland during an unfavorable season.

The defensive success of the citadel was a powerful psychological victory for the Nguyễn, demonstrating their ability to penetrate Tây Sơn territory at all times of year. The Nguyễn then proceeded to slowly erode the Tây Sơn heartland.

Heavy fighting occurred at the fortress of Qui Nhơn until it was captured in 1799 by Nguyen Canh's forces. However, the city was quickly lost and was not regained until 1801. The superior firepower of the improved navy played the decisive role in the ultimate recapture of the city, supporting a large overland attack.

After the capture of their stronghold at Qui Nhơn the end of the Tây Sơn came quickly. In June, the central city of Huế, the former capital of the Nguyễn, fell and Nguyễn Ánh crowned himself emperor, under the reign name Gia Long, which was derived from Gia Định (Saigon) and Thăng Long (Hanoi) to symbolize the unification of northern and southern Vietnam.

He then quickly overran the north, with Hanoi captured on 22 July 1802. After a quarter-century of continuous fighting, Gia Long had unified what is now modern Vietnam and elevated his family to a position never previously occupied by Vietnamese royalty. Vietnam had never before occupied a larger landmass.

Gia Long became the first Vietnamese ruler to reign over territory stretching from China in the north, all the way to the Gulf of Siam and the Cà Mau peninsula in the south. Gia Long's then petitioned the Qing dynasty of China for official recognition, which was promptly granted.

The French failure to honor the treaty signed by Pigneau meant Vietnam was not bound to cede the territory and trading rights that they had promised. Due to a Tây Sơn massacre against ethnic Chinese, the Nguyễn were supported by ethnic Chinese against the Tây Sơn.

The Tây Sơn's downfall and defeat at the hands of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh was due in part to ethnic Chinese support to the Nguyễn. Gia Long's rule was noted for its strict Confucian orthodoxy. Upon toppling the Tây Sơn, he repealed their reforms and reimposed a classical Confucian education and civil service system.

He moved the capital from Hanoi in the north to Huế in central Vietnam to reflect the southward migration of the population over the preceding centuries. The emperor built new fortresses and a palace in his new capital.

Using French expertise, Gia Long modernized Vietnam's defensive capabilities. In deference to the assistance of his French friends, he tolerated the activities of Catholic missionaries, something that was increasingly restricted by his successors.

Under Gia Long's rule, Vietnam strengthened its military dominance in Indochina, expelling Siam from Cambodia and turning it into a vassal. Despite this, he was relatively isolationist in outlook towards European powers.

Renaming Vietnam - Gia Long decided to join the Imperial Chinese Tributary System. He sent an embassy to Qing China, and requested to change his country's name to Nam Việt (南越).

Gia Long explained that the word Nam Viet derivated from An Nam (安南) and Viet Thường (越裳), two toponyms mentioned in ancient Chinese records where located in northern and southern Vietnam respectively, to symbolize the unification of the country.

The Qing Jiaqing Emperor of China refused his request because it had identical name with the ancient kingdom Nam Viet (Nanyue), and the territory of Nam Viet contained Liangguang where belonged to Qing China in that time. Instead, Jiaqing agreed to change it to Viet Nam (越南). Gia Long's Đại Nam thực lục contains the diplomatic correspondence over the naming.

However, Gia Long copied the Imperial Chinese system, declaring himself on the Chinese Confucian model and attempting to create a Vietnamese Imperial tributary system. "Trung Quốc" (中國)[g] was used as a name for Vietnam by Gia Long in 1805.

Herman Goring's daughter

It was said "Hán di hữu hạn" (漢夷有限, "the Vietnamese and the barbarians must have clear borders") by the Gia Long Emperor (Nguyen Phúc Ánh) when differentiating between Khmer and Vietnamese.

Minh Mạng implemented an acculturation integration policy directed at minority non-Vietnamese peoples. Thanh nhân (清人) was used to refer to ethnic Chinese by the Vietnamese while Vietnamese called themselves as Hán nhân (漢人) in Vietnam during the 1800s under Nguyen rule.

Lê Văn Duyệt, the longest-serving and the last military protector of the four provinces of Cochinchina - During the war era, Nguyễn Ánh had maintained an embryonic bureaucracy in an attempt to prove his leadership ability to the people.

Due to the incessant warfare, military officers were generally the most prominent members of his inner circle. This dependency on military backing continued to manifest itself throughout his reign. Vietnam was divided into three administrative regions.

The old patrimony of the Nguyễn formed the central part of the empire (vùng Kinh Kỳ), with nine provinces, five of which were directly ruled by Gia Long and his mandarins from Huế. The central administration at Huế was divided into six ministries: Public affairs, finance, rites, war, justice and public works.

Each was under a minister, assisted by two deputies and two or three councillors. Each of these ministries had around 70 employees assigned to various units. The heads of these ministries formed the Supreme Council.

A treasurer general and a Chief of the Judicial Service assisted a governor general, who was in charge of a number of provinces. The provinces were classified into trấn and dinh. These were in turn divided into phủ, huyện and châu.

All important matters were examined by the Supreme Council in the presence of Gia Long. The officials tabled their reports for discussion and decision-making. The bureaucrats involved in the Supreme Council were selected from the high-ranking mandarins of the six ministries and the academies.

Gia Long handled the northern and southern regions of Vietnam cautiously, not wanting them to be jarred by rapid centralization after centuries of national division.

Tonkin, with the administrative seat of its imperial military protector (quan tổng trấn) at Hanoi, had thirteen provinces (tổng trấn Bắc Thành), and in the Red River Delta, the old officials of the Le administration continued in office.

In the south, Saigon was the capital of the four provinces of Cochinchina (tổng trấn Nam Hà), as well as the seat of the military protector. The citadels in the respective cities directly administered their military defense zones.

This system allowed Gia Long to reward his leading supporters with highly powerful positions, giving them almost total autonomy in ordinary administrative and legal matters. This system persisted until 1831–32, when his son Minh Mạng centralized the national government.

In his attempts to re-establish a stable administration after centuries of civil war, Gia Long was not regarded as being innovative, preferring the traditional administration framework. When Gia Long unified the country, it was described by Charles Maybon as being chaotic:

"The wheels of administration were warped or no longer existed; the cadres of officials were empty, the hierarchy destroyed; taxes were not being collected, lists of communal property had disappeared, proprietary titles were lost, fields abandoned; roads bridges and public granaries had not been maintained; work in the mines had ceased.

The administration of justice had been interrupted, every province was a prey to pirates, and violation of law went unpunished, while even the law itself had become uncertain."

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Cambodian empire had been in decline and Vietnamese people migrated south into the Mekong Delta, which had previously been Khmer territory. Furthermore, Cambodia had been periodically invaded by both Vietnam and Siam.

Cambodia lurched uneasily between both poles of domination as dictated by the internal strife of her two larger neighbors. In 1796, Ang Eng, a pro-Siamese king had died, leaving Ang Chan, who was born in 1791.

When Gia Long unified Vietnam, Eng was given investiture by Siam in order to hold out Vietnamese influence, but in 1803, a Cambodian mission paid tribute to Vietnam in attempt to placate Gia Long, something that became an annual routine.

In 1807, Ang Chan requested formal investiture as a vassal of Gia Long. Gia Long responded by sending an ambassador bearing the book of investiture, together with a seal of gilded silver.

In 1812, Ang Chan refused a request from his brother Ang Snguon to share power, leading to a rebellion. Siam sent troops to support the rebel prince, hoping to enthrone him and wrest influence from Gia Long over Cambodia.

In 1813, Gia Long responded by sending a large military contingent that forced the Siamese and Ang Snguon out of Cambodia. As a result, a Vietnamese garrison was permanently installed in the citadel at Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital. Thereafter, Siam made no attempts to regain control of Cambodia during Gia Long's rule.

Napoleon's aims to conquer Vietnam as a base to challenge British supremacy in India never materialized, having been preoccupied by vast military ambitions on mainland Europe. However, France remained the only European power with permanent spokesmen in Vietnam during his reign.

Pigneau's aborted deal with France allowed Gia Long to keep his country closed to western trade. Gia Long was generally dismissive of European commercial overtures. This was part of a policy of trying to maintain friendly relations with every European power by granting favors to none.

In 1804, a British delegation attempted to negotiate trading privileges with Vietnam. It was the only offer of its kind until 1822, such was the extent of European disinterest in Asia during the Napoleonic Wars.

Gia Long had purchased arms from British firms in Madras and Calcutta on credit, prompting the British East India Company to send John Roberts to Huế. However, Roberts's gifts were turned away and the negotiations for a commercial deal never started.

The United Kingdom then made a request for the exclusive right to trade with Vietnam and the cession of the island of Cham near Faifo, which was rejected, as were further approaches from the Netherlands.

Both of these failed attempts were attributed to the influence of the French mandarins. In 1817, the French Prime Minister Armand-Emmanuel du Plessis dispatched the Cybele, a frigate with 52 guns to Tourane (now Da Nang) to "show French sympathy and to assure Gia Long of the benevolence of the King of France".

The captain of the vessel was turned away, ostensibly on grounds of protocol for not carrying a royal letter from the French king. Gia Long kept four French officers in his service after his coronation: Philippe Vannier, Jean-Baptiste Chaigneau, de Forsans and the doctor Despiau. All became high ranking mandarins and were treated well.

They were given 50 bodyguards each, ornate residences and were exempt for having to prostrate before the emperor. Recommendations from French officials in Pondicherry to Napoleon Bonaparte suggesting the re-establishment of diplomatic relations with Vietnam were fruitless due to the preoccupation with war in Europe.

However, French merchants from Bordeaux were later able to begin trading with Vietnam after the further efforts of the Duc de Richelieu. Jean-Marie Dayot (left) took a leading role in the training of Gia Long's navy - Gia Long abolished all large landholding by princes, nobles and high officials.

He dismantled the 800-year-old practice of paying officials and rewarding or endowing nobles with a portion of the taxes from a village or a group thereof. Existing highways were repaired and new ones constructed, with the north-south road from Saigon to Lạng Sơn put under restoration.

He organised a postal service to operate along the highways and public storehouses were built to alleviate starvation in drought-affected years. Gia Long enacted monetary reform and implemented a more socialized agrarian policy.

However, the population growth far outstripped that of land clearing and cultivation. There was little emphasis on innovation in agricultural technology, so the improvements in productivity were mainly derived from increasing the amount of cultivated farmland.

Although the civil war was over, Gia Long decided to add to the two citadels that had been built under the supervision of French officers. Gia Long was convinced of their effectiveness and during his 18-year reign, a further 11 citadels were built throughout the country.

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100008470757951

The majority were built in the Vauban style, with pentagonal or hexagonal geometry, while a minority, including the one in Huế, were built in a four-sided traditional Chinese design.

The fortresses were built at Vinh, Thanh Hóa, Bắc Ninh, Hà Tĩnh, Thái Nguyên and Hải Dương in the north, Huế, Quảng Ngãi, Khánh Hòa and Bình Định in the centre, and Vĩnh Long in the Mekong Delta. Construction was at its most intense in the early phase of Gia Long's reign, only one of the 11 was built in the last six years of his rule.

Emperor Duy Tân, born Nguyễn Phúc Vĩnh San, was an emperor of the Nguyễn Dynasty who reigned for 9 years between 1907 and 1916.

De Puymanel and Lebrun left Vietnam before the end of the war, so the forts were designed by Vietnamese engineers who oversaw the construction. The position of Citadel Supervision Officer was created under the Ministry of War and made responsible for the work, underlining the importance that Gia Long placed on fortifications.

Gia Long's fortifications program was marred by accusations that the people labored all day and part of the night in all weather conditions, and that as a direct consequence, land went fallow. Complaints of mandarin corruption and oppressive taxation were often levelled at his government.

My grandfather used used to go fishing in Pulau Bidong. And he said some of the fishes will be distributed to Refugees, order from the Terengganu Red Crescent Authority. We live near the jetty to Pulau Bidong.

Following his coronation, Gia Long drastically reduced his naval fleet and by the 1810s, only two of the European-style vessels were still in service. The downsizing of the navy was mainly attributed to budgetary constraints caused by heavy spending on fortifications and transport infrastructure such as roads, dykes and canals.